This weekend I was glad to speak at the Ignite Conference 2022, a collaborative initiative of the Emmanuel Community and our Sydney Centre for Evangelisation in the Archdiocese of Sydney.

I addressed the theme of “leading change”, speaking to the personal and ecclesial aspects of moving our communities and ministries toward a genuine missionary stance. I touched on the role of charism in leading and responding to change, and the personal challenges that leadership evokes in the Church today and supports for a ministry that is both sustainable and fruitful for Christ’s mission.

I am conscious of the many different and varied contexts in which we lead, whether we exercise influence in our local parishes or dioceses, schools, ecclesial movements or other communities of faith. One consequence of this is that the responsibilities of leadership that we hold will differ and so will the particular dynamics of leading change.

However, what these forms of leadership will hold in common is that they will ultimately be concerned with exercising effective influence towards a particular goal. More specifically, as Catholic leaders our goal will be in related to proclaiming and witnessing to God’s love given to us in Jesus Christ and engage the task of bringing people into the encounter, surrender and the decision of faith. As leaders in the Church, we are called to be fruitful and make Christ’s life and mission powerfully present in our time with the people and communities that we serve.

Leadership for mission, then, will not be primarily a rank or position but a choice and responsibility to actively serve a goal that is greater than ourselves.

Leadership Matters

Before examining the issues that arise when leading change in the Church, it is important to affirm that courageous leadership matters a great deal for the future of our Church and its presence in the world as a real sign and presence of Christ.

In the Scriptures, Christ himself holds up leadership as essential to the continuation of his mission. Amidst the teeming crowds seeking out his help, Jesus still took the time to gather a group of leaders around him: forming, correcting and inspiring them; calling them into deeper discipleship; helping them to understand what impeded their leadership; and creating a culture of leadership as service.

We know that Jesus expressed compassion for people who did not have leaders: “He saw a great crowd; and he had compassion for them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd” (Mk 6:34). Jesus was critical of those who exercised their leadership without a spirit of service, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. It will not be so among you…” (Matt. 20:25) and he rebuked those who evaded responsibility or led with impure motive, “They tie up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on the shoulders of others; but they themselves are unwilling to lift a finger to move them. They do all their deeds to be seen by others” (Matt. 23:4-5).

More positively, Jesus makes clear that all those who encounter him are given a commission to lead others to Him and to work toward the self-giving love, justice, forgiveness and abundance that marks God’s Kingdom. This pattern in Scripture is unmistakeable: those who experience a profound encounter with God are then given a mission to lead others to God.

As example, St Peter encounters Jesus in the miraculous catch and is called to follow Him and become a “fisher of men” (Matt. 4:19). Likewise, St Paul has a blinding encounter with Jesus on the road to Damascus and is then called into God’s service in such a profound way that he proclaims, “Woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel!” (1 Cor. 9:16). Clearly, leadership matters and is expected of us in extending the mission of Christ in every age.

Varieties of Leadership

It is important to affirm that the various forms of leadership that Christ gives to the Church for this mission do not compete with one another. Properly understood and exercised, these varieties of leadership and influence work together to build up the one Body of Christ.

For instance, our priests are most often responsible for the oversight, pastoral care and leadership of our parishes and chaplaincies. They teach the Catholic faith, sanctify through the sacraments and other rites of the Church and, in union with the bishop, build up the communion of the Church so it can be a convincing sign of Christ in the world.

We have consecrated men and women as well who express for the Church the primacy of the Holy Spirit in Christian life, a Spirit who manifests within the life of a specific religious order or community the fact that Christian discipleship is possible even in this way. These religious communities with their varied charisms and expressions remind us that diversity can be an expression of God’s life too.

There are also many lay leaders who lead and direct various pastoral works of the Church, who engage in ecclesial ministry in our parishes as youth ministers, sacramental coordinators, catechists, leaders of prayer groups and ministries, as well as in our Catholic schools, universities and other educational institutions. Lay people today oversee and lead our hospitals and healthcare facilities, welfare and social support services, and the Church’s outreach to the poor and vulnerable.

Then, there is the leading witness that all the baptised exercise in daily life, with the Spirit’s gifting we find described in the New Testament, particularly in Romans, 1 Corinthians and Ephesians. In his correspondence to the Christians at Ephesus, now the Izmir province in Turkey, St Paul writes, “The gifts He gave were that some would be apostles, some prophets, some evangelists, some pastors, and some teachers, to equip the saints for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ” (Eph. 4:11-12). We are gifted differently and so will lead change differently.

The apostles among us will be the visionaries who extend the Gospel, who can be found most often thinking and asking questions about the future and dreaming about what could be. They are our Peters, Priscillas and Aquillas.

Our prophets are those who prioritise listening to God, who enjoy time alone with God, who wait, listen and call people to obey God’s will, like Isaiah, Jeremiah and John the Baptist. Our prophets value holiness, obedience and God’s revelation.

The evangelists among us enjoy talking to others about the life of Jesus and will have a primary concern to ensure new people are discovering and entering into Christ’s life and the Church. They enjoy discussions with those who are not Christians or far from the Church and are focused on inviting ‘outsiders’ in.

In experience, many of the people in our communities tends to be shepherds. Shepherds enjoy one-on-one chats and helping others; they tend to lead with care, counsel, empathy and encouragement, much like Barnabas and James. They nurture and protect and are the caregivers of the community, focused on the interrelationships and spiritual maturity of God’s flock.

Our teachers are explainers of God’s truth and wisdom. They relish helping others understand the Gospel and the traditions and teachings of the Church and to apply this learning to their lives, much like Apollos and Philip.

So, each of us are gifted in our own way, and each of us will tend to lead and indeed respond to change in accordance with our gifts and charisms. More often than not, we will lead change most effectively in our Church when we lead change alongside others who have different but complementary gifts to our own.

For example, the visionary apostle often needs the presence of care that the shepherd brings so people are cared for rather than merely dragged along on a journey they are not accustomed to or comfortable with, and apostles also need prophets alongside them, so they are attentive to God and not acting purely on their own strength.

In my experience, when leading change in the Church, and specifically in our parishes, we will be challenged by leading change among a high proportion of ‘shepherds’, people who are the caregivers in community and prize stability and the interrelationships of a community. The great gift of shepherds is that they like to be with people in their lives, their brokenness and pain, and are highly empathetic. However, shepherds can also have difficulty moving people from that stage of life to the next stages of discipleship – to conversion of life, repentance and transformation. Shepherds may lack the confidence to challenge people to move forward, for fear that the person will be angry or upset with them.

Similarly, leading change with ‘shepherds’ can be challenging because people gifted in this way tend to value stability and have a natural desire to avoid any negative impact on others. In light of this, shepherds usually benefit from having an apostle or evangelist alongside them to keep the mission moving forward, or else a prophet by their side to ensure the truth is spoken and people are being called to conversion, even when it is hard.

However, the great gift of shepherds to the Church and leaders of change is that they can teach those who may be apostles or evangelists, who like movement and are eager to embrace ‘the new’ or untried, to minimise pain in the process of change and to be more attentive to the impact change can have on a community and their networks of relationship.

The Need to Lead Change

Having recognised the different ways in which people will lead according to their gifts, we turn to the specific challenge of leading change. Change is a fact occurring around us and within us, and indeed there is no growth personally or for the Church as a whole without change.

Take the challenge of change among our parishes for instance. Whether one is a priest, deacon, lay leader in parish ministry or a youth leader, the plain fact is that our parishes have not grown in roughly seven decades in Australia, since at least the 1950s. The majority of our parishes in Australia continue to decline each and every year. If our purpose as a Church is to evangelise, to proclaim the Gospel of Jesus Christ to the people of this time, place and culture, then we cannot keep doing what we’ve always done and expect a different result.

When our local communities have been declining for decades, it is going to be inevitable that there will be a small amount of people who love how we do things as Church and as leaders in the Church, and a whole community out there who don’t.

If we want to be more effective in reaching people for Christ, we are called to re-evaluate. We are called to re-evaluate not the Gospel – the life of Jesus himself who remains the same yesterday, today and forever (Hebrews 13:8) – but the ways, methods and expressions by which we bring this Gospel or ‘Good News’ closer to the people of our time. In short, all of us as leaders need to confront the challenge of changing how we do things to be ever more faithful and fruitful to Christ.

Whether we are wrestling with declining numbers in our pews; changing priorities, expectations or demographics within our Catholic schools; changes perhaps in the available resources at your disposal or personnel or volunteers for shared ministry and service; or responding to new developments in the life of our Church or within the wider community, good leadership in the Church today means leading change. In fact, it can be said that if we as leaders in the Church are not leading change, we are probably not leading at all. By very definition, to lead means taking a team, a ministry, a community, and ourselves from one point to another.

We have been tasked by Christ to grow the Church, to ‘go, make disciples of all nations’ (Matthew 28:19). When the landscape of faith in Australia is changing – when less people are close to the Church or Gospel than in previous generations, when more people claim no religious affiliation – we cannot afford to read off old maps. We are called to renew and change our approaches to evangelisation and outreach for the sake of the Gospel. This has been the pattern for the Church throughout the ages – adapting itself time and again to better proclaim and witness to the abiding Gospel and in full contact with the circumstances of its time.

It can be sobering for our communities, ministries and organisations to realise that they are perfectly structured and set up to achieve the results they are currently getting. If we want something other than the status quo, then we have to be prepared to change. Too often in Christian life we want God to do something new while we remain the same!

Leading change means making decisions about which direction our ministry or community should go, changing practices and methods to better fulfil our mission, reflecting on how to take others with us in that change, how to respond to the inevitable challenges and even resistance we can encounter in leading change, and how to sustain ourselves spiritually and otherwise throughout this process.

Preparing for Change

For many of us seeking to lead change in the Church – whether that change is big or small – we will inevitably find ourselves caught between an experience of a call and desire for renewal and the weight of church culture towards maintaining the status quo. In such an environment, it is important we do not become discouraged or disillusioned in the process of leading the growth and renewed vitality we all want to see in the Church.

It is worth noting that when we see people ‘burn out’ or become disillusioned in Church ministry, or even in their careers or vocations for that matter, it often has much less to do with how that person deals with the changes in their external environment and much more to do with how a person deals with themselves in the midst of that environment. After all, as the COVID-19 pandemic and our life more broadly will teach us, the only thing over which we can exert much control is our response to change, not the circumstances that surround us.

So leading change is inherently challenging and self-implicating as it will test our character, what we value and believe within, how we respond to difficulties, relate with others, and understand ourselves before God.

In leading change in the Church, it is always helpful to remind ourselves from the outset that the mission of our parish, diocese, or ministry does not all depend on us and that the Holy Spirit is always the primary agent of evangelisation, the one who bears the fruit and gives the growth, with whom we cooperate rather than substitute. It is equally important that we as leaders do not ‘spiritualise’ a lack of effort or fruitfulness in our ministry, and that we dedicate ourselves to making the very most of the gifts God has given us to serve God’s purposes. This means reflecting on and attending to a few key strategies so we can lead change well.

Articulating our Reality

One of the practical things we can do in leading change well is to understand the landscape we are seeking to shape and influence. This is important because we want to build new approaches and strategies for mission on firm ‘rock’ rather than sand so to speak.

One of the best preparations for leading change in any organisation or community of the Church is to establish a clear view of reality, a firm and foundational understanding of the dynamics at play in a given scenario. This is especially important when the community or ministry we are trying to grow or change is complex or in crisis, which some would argue describes the current state of the Church.

As an analogy, when a building is on fire or some other unexpected event occurs, the role of the leader is to give a clear account of what has taken place, working together with allies to convey this clear picture of reality. When the spokesman or woman comes forward to share what happened before a burning shop front, they exercise leadership simply by the act of describing reality for those trying to make sense of the scene (and without having done very much else!).

In a world of ‘fake news’ and fast online opinions, it is important to recognise a significant part of mature leadership is seeing the circumstances or situation we seeking to impact with clarity and depth. In other words, leading change involves doing some ‘homework’ or research and taking care and time to establish the facts. Leaders who have only half of the facts in hand or tend to be reactive or impulsive in response to situations can lead change that can be ineffective or even damaging. Their intent can be good, but their impact can be terrible. As the saying goes, “for every complex problem there are solutions that are simple, clear and wrong”. For a community as complex and important as the Church, there are few if any ‘silver bullets’ and this means engaging the full complexity of a scene rather than only the parts we want to see.

For instance, when leaders turn to address the reality of declining Mass attendance in our Church, it can be all too tempting to put this at the feet of poor preaching, bad music and unfriendly people. It is true that these internal factors can discourage people’s engagement with our parishes and addressing these issues is pivotal. However, the reality is that people’s disengagement can also be the result of external factors, chief among them sport or other personal priorities at the weekend, or an unsupportive spouse or children. In short, disengagement from worship can be influenced by factors which have little to do with the experience of the parish in the pews as such.

How we define a pastoral problem and understand its causes will shape the responses we pursue in leading change. Building solutions on oversimplified, only partial or erroneous understandings of the present can lead to poor responses or, at the very least, incomplete ones that may not bear the full fruit we want to see.

Casting Vision

Complementing a firm grasp of the current reality is the need for leaders of mission to cast and unpack with their people a compelling vision of what the future could look like if change was realised and to bring others into this vision of a better future.

Again, as example, here in the Archdiocese of Sydney the key change we have identified as being at the heart of increased participation in worship, growing income and resources for our parishes, and increased support of volunteers and parish personnel is the growth of personal discipleship. Parishes change and grow only when people change and grow.

However, in casting this vision with our parishes we were conscious that if nobody in our parishes, or Church agencies for that matter, talks about what Christian discipleship looks like, it becomes difficult for people to begin to walk on that road. As Sherry Weddell notes, “Unfortunately, most of us are not spiritual geniuses. If nobody around us ever talks about a given idea, we are no more likely to think of it spontaneously than we are to suddenly invent a new primary colour. To the extent we don’t talk explicitly with one another about discipleship, we make it very, very difficult for most Catholics to think about discipleship” (Sherry Weddell, Forming Intentional Disciples). It is difficult to believe in and live something that you have never heard anyone talk about.

In the same way, reviewing our local parishes, youth groups, ministries and communities will remain a theory unless we have clear and consistent leadership that communicates a vision and inspires the engagement of the whole community in that vision for Christ.

In forming our vision, Pope Francis has called us repeatedly to expand our vision beyond a narrow concern for self-preservation and to embrace a vision of evangelisation, reaching out beyond ourselves to seek out all those who are lost. If we are leading a ministry or community today and outreach to those who are not Christians or are otherwise far from the Church is not part of its vision, the lifespan of that ministry or community is already limited before it has even begun.

A clear vision for evangelisation – for making “missionary disciples” as Pope Francis puts it – is a necessity to maintain even what we have as local communities of faith. This is obvious enough in the struggle to maintain our ministries, our giving and even, in some parishes and ministries, our hope. More positively, when we bring new people to Jesus and the Church it plants energy and life in our communities.

While we as communities and ministries can naturally tend to focus on the flock or the sheep we do have, there is an increasing recognition that the sheep are not having ‘baby sheep’ and that we will have to learn a new skill set in this age which is actually an ancient one. We need to learn to ‘fish’ like the first disciples of Jesus and cast our nets far, rather than ‘making do’ with a slowly diminishing flock. Leading change in such a way that attends to the unchurched and those far from the Gospel aligns with the saving mission of Jesus who comes not for the righteous but for sinners, who places the needs of the outcast and ailing even before his own flock, a focus that, paradoxically, renews the flock and reminds the sheep of what it means to follow Him.

Addressing Resistance

Having talked about the importance of a clear view of the pastoral reality and casting a compelling vision for a preferred future, one of the realities for all leaders who are leading change is the likelihood of resistance. Change always sounds great until people start to experience it!

When we encounter resistance to change that we as leaders have either proposed or introduced, it can be helpful to realise the source of that resistance is not usually a lack of vision but in fact too many visions. As noted earlier, all of our people will have a different experience and perspective of Christian life – some will be apostles who are open and eager to break new ground, others are teachers who want their community to be primarily a school of faith where people learn and think, while others envision the Church as called primarily to offer the embrace of a sheepfold, to privilege care and nurturance of the flock.

The upshot of all these perspectives is that some in our communities will find proposals for change that might propose unnecessary, alarming or a threat, as misdirected, or wasteful of time and money. Unless it is a really terrible idea, we will usually have some supporters, alongside a good number of people in the ‘middle’ who prefer a ‘wait and see’ approach, while the remainder will be indifferent, resistant or opposed.

In managing such community dynamics as leaders of change, we should be careful not to treat these cohorts the same. Time and again, it has been shown that giving too much oxygen to the vocal minority who tend to oppose change can take up enormous amounts of limited energy for little gain and these negative forces can drag others in the ‘middle‘ with them. In experience, leaders of change often focus on investing in and galvanising the ‘supporters’ for the change, the ‘early adopters’ who can influence and engage those in the ‘middle’ toward greater openness and engagement with the intended change.

This is not to say that we should entirely ignore the voices of those who oppose change as there is usually some aspect of truth that can be found even in those who might be most resistant. It is important to remember in leading change that behind every program or initiative that has had its day, or from which we need to move on, close or amend, there are real people and convictions. One of the proper responsibilities of leading change is to minimise the pain of change and to ensure as many people are included in the new direction or approaches that we pursue.

Sustaining Our Leadership

I wanted to conclude by addressing the issue of resilience in leading change as burn out, disillusionment and discouragement can impact upon many leaders in the Church seeking to move a community or ministry group from one point to another. Our reactions to the criticisms we might face or the challenges we might endure will often force us to face up to our inner motives; those things that are of ultimate value to us; even our beliefs about God, ourselves and others.

However, leadership is not a journey that is meant to be travelled alone and the necessary supports of a regular sacramental life and constant prayer, professional supervision, the company and understanding of peers, and some form of mentoring or coaching can also help us and save us unnecessary pain. As it is said, ‘self-experience can a brutal teacher’ and learning from others who can mentor and guide us from their own experience of change can save us unnecessary hardship.

We also need to develop a clear sense of the boundaries of our responsibilities – what is within our control and influence, and what is beyond it and for which we need not take responsibility. A reliance on prayer and a healthy surrender to grace and the providence of God in our daily efforts can give us the confidence to lead boldly while remaining open and humble before God and others, a spirit that echoes the trust of Christ in the Father and the great saints who were led by the Spirit, exercised their gifts and were ultimately faithful, even in trial and tribulation, to God’s purposes.

I close with this encouragement from the First Letter of St Peter, which reminds us, “Whoever serves must do so with the strength that God supplies, so that God may be glorified in all things through Jesus Christ” (1 Peter 4:11). This divine life is the source of all authentic change in our Church and the source of our joy in our cooperation with God in leading change.

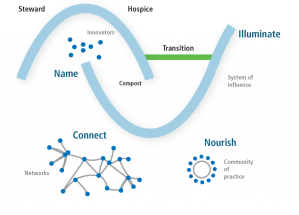

workshop will extend the theme of ‘missionary discipleship’ to consider how youth ministry can support young people to move and grow from participation in youth ministry to exercise their discipleship as adults in broader parish and community life. If youth ministry gathers for the purpose of sending out, how can our ministries best prepare young people for that future? One of the claims of this workshop is that if we can identify the issues of our moment, and we know the destination at which we want to arrive, then this will shape the steps we can take to get there. If our purpose is sending young people out into mission, into the full life of the Church and world, then how does our youth ministry best prepare them for that future?

workshop will extend the theme of ‘missionary discipleship’ to consider how youth ministry can support young people to move and grow from participation in youth ministry to exercise their discipleship as adults in broader parish and community life. If youth ministry gathers for the purpose of sending out, how can our ministries best prepare young people for that future? One of the claims of this workshop is that if we can identify the issues of our moment, and we know the destination at which we want to arrive, then this will shape the steps we can take to get there. If our purpose is sending young people out into mission, into the full life of the Church and world, then how does our youth ministry best prepare them for that future?

The poet Gerard Manly Hopkins developed this term ‘inscape’ for the individual structure of a living being (like a tree or a leaf), an inner structure which results from the history of this being, an inner design made by the tree through its life in the way it has responded to life. We are much the same, our life is a work of art and all the good and the bad, conflicts and sufferings, troubles and happiness in our life all add up to something, all produce this inner structure, and this is what we are judged on, our encounter with Jesus and the direction that we chose to live. We are judged not on small incidentals (eating meat on Fridays) but rather the whole structure of our life – all that we wanted to do, tried to do, our relationships. This all adds up to our identity which God knows. Hence the value of youth ministers as spiritual guides who can help the next generation to be in touch with the whole direction and meaning of their life as a whole, what it is all adding up to and to encourage them to develop in this direction and not another.

The poet Gerard Manly Hopkins developed this term ‘inscape’ for the individual structure of a living being (like a tree or a leaf), an inner structure which results from the history of this being, an inner design made by the tree through its life in the way it has responded to life. We are much the same, our life is a work of art and all the good and the bad, conflicts and sufferings, troubles and happiness in our life all add up to something, all produce this inner structure, and this is what we are judged on, our encounter with Jesus and the direction that we chose to live. We are judged not on small incidentals (eating meat on Fridays) but rather the whole structure of our life – all that we wanted to do, tried to do, our relationships. This all adds up to our identity which God knows. Hence the value of youth ministers as spiritual guides who can help the next generation to be in touch with the whole direction and meaning of their life as a whole, what it is all adding up to and to encourage them to develop in this direction and not another. Held in Brisbane for the first time in its short history, Proclaim Conference 2018 gathered more than 600 participants from 12-14 July to discuss parish evangelisation with its theme drawn from John’s Gospel, “Make your home in me”. Keynote speakers over the three days included Archbishop Mark Coleridge, Cardinal John Dew from Wellington, Ron Huntley of the Divine Renovation network, Karolina Gunsser from Citipointe Church in Redcliffe, and Lana Turvey-Collins from the national facilitation team for the Plenary Council.

Held in Brisbane for the first time in its short history, Proclaim Conference 2018 gathered more than 600 participants from 12-14 July to discuss parish evangelisation with its theme drawn from John’s Gospel, “Make your home in me”. Keynote speakers over the three days included Archbishop Mark Coleridge, Cardinal John Dew from Wellington, Ron Huntley of the Divine Renovation network, Karolina Gunsser from Citipointe Church in Redcliffe, and Lana Turvey-Collins from the national facilitation team for the Plenary Council. As a former ‘outsider’ to the Church it has taken some twenty years to learn to live as a baptised person and still the learning continues. Through my own faith experience I have come to believe that the parish is essential to Christian growth and discipleship. Indeed, if we did not have parishes we would have to invent them – local communities of faith gathered around the Word and Eucharist where faith is given shape and social support, fostered into discipleship and then enters the world through our living witness.

As a former ‘outsider’ to the Church it has taken some twenty years to learn to live as a baptised person and still the learning continues. Through my own faith experience I have come to believe that the parish is essential to Christian growth and discipleship. Indeed, if we did not have parishes we would have to invent them – local communities of faith gathered around the Word and Eucharist where faith is given shape and social support, fostered into discipleship and then enters the world through our living witness. The Church is not for ourselves. In Pope Francis’ language, our community is called to be a ‘field hospital’ serving those who most need help now, the wounded and the lost. This is the antithesis of the self-referential Church. We are called to leave the ninety-nine to find the one, or in our Australian reality, leave the one to find the ninety-nine.

The Church is not for ourselves. In Pope Francis’ language, our community is called to be a ‘field hospital’ serving those who most need help now, the wounded and the lost. This is the antithesis of the self-referential Church. We are called to leave the ninety-nine to find the one, or in our Australian reality, leave the one to find the ninety-nine. In fact, inward looking churches create consumers with preferences, while outward looking churches create missionaries with larger hearts and stories to tell, stories about how Jesus has changed their life. This is the heart of an evangelised parish culture – one beggar telling another beggar how he found bread.

In fact, inward looking churches create consumers with preferences, while outward looking churches create missionaries with larger hearts and stories to tell, stories about how Jesus has changed their life. This is the heart of an evangelised parish culture – one beggar telling another beggar how he found bread. A classic example of the need to prioritise our mission over method can be found in the story of Kodak, the photography business established at the turn of the twentieth century, with the expressed purpose of preserving memories which is a seemingly indestructible mission.

A classic example of the need to prioritise our mission over method can be found in the story of Kodak, the photography business established at the turn of the twentieth century, with the expressed purpose of preserving memories which is a seemingly indestructible mission. A third horizon we can move toward in forming evangelising parishes is structures that support the mission. We want to grow but many parishes are not necessarily structured to grow. There can be literally “no room in the inn” for change.

A third horizon we can move toward in forming evangelising parishes is structures that support the mission. We want to grow but many parishes are not necessarily structured to grow. There can be literally “no room in the inn” for change. The fourth horizon we can move towards is putting mission into action, perhaps the hardest pilgrimage of all. As a friend once shared, conferences can sometimes be a bit like this: “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit” and when we get home, it is more “… as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be, world without end”.

The fourth horizon we can move towards is putting mission into action, perhaps the hardest pilgrimage of all. As a friend once shared, conferences can sometimes be a bit like this: “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit” and when we get home, it is more “… as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be, world without end”. One of the catchcries of Pope Francis’ vision for a renewed missionary outreach by Christians is the concept of ‘accompaniment’. It is a word that might be familiar to us in the context of music, in which one part adds, supports or complements another, or else in the sphere of gastronomy where wine is said to ‘accompany’ cheese. In fact, a quick Google search reveals the third highest query for the term ‘accompaniment’ relates to the most suitable garnishes for fish!

One of the catchcries of Pope Francis’ vision for a renewed missionary outreach by Christians is the concept of ‘accompaniment’. It is a word that might be familiar to us in the context of music, in which one part adds, supports or complements another, or else in the sphere of gastronomy where wine is said to ‘accompany’ cheese. In fact, a quick Google search reveals the third highest query for the term ‘accompaniment’ relates to the most suitable garnishes for fish! We find a few scant references to accompaniment in Pope Francis’ exhortation on marriage and family Amoris Laetitia, especially in relation to those in the early years of marriage and those who have experienced relationship breakdown or divorce (AL 223, 241-244). The concept is most fully elaborated, however, in Pope Francis’ first Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium (‘The Joy of the Gospel’) where we find four articles dedicated to what he describes as the “art of accompaniment” (EG 169-173). These references are in the third chapter of the Exhortation, under the fourth section entitled “Evangelization and the deeper understanding of the kerygma”.

We find a few scant references to accompaniment in Pope Francis’ exhortation on marriage and family Amoris Laetitia, especially in relation to those in the early years of marriage and those who have experienced relationship breakdown or divorce (AL 223, 241-244). The concept is most fully elaborated, however, in Pope Francis’ first Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium (‘The Joy of the Gospel’) where we find four articles dedicated to what he describes as the “art of accompaniment” (EG 169-173). These references are in the third chapter of the Exhortation, under the fourth section entitled “Evangelization and the deeper understanding of the kerygma”. Pope Francis has commented that we in the twenty-first century live not simply in an ‘age of change’ but in a ‘change of age’. He sees, as we do, the shifting ground of global politics, the movements of people around the world, including a disastrous refugee crisis, and the changing nature of how people communicate and relate to one another (to make the point, each day the equivalent of 110 years of live content is watched online while development such as OTT apps have essentially turned messaging services into a new form of communications infrastructure).

Pope Francis has commented that we in the twenty-first century live not simply in an ‘age of change’ but in a ‘change of age’. He sees, as we do, the shifting ground of global politics, the movements of people around the world, including a disastrous refugee crisis, and the changing nature of how people communicate and relate to one another (to make the point, each day the equivalent of 110 years of live content is watched online while development such as OTT apps have essentially turned messaging services into a new form of communications infrastructure). Turning from the wider community to our Church, our own community of faith is also changing and this can felt at the front doors of our parishes – in the variety of people we now encounter with different situations, questions and expectations than in the past.

Turning from the wider community to our Church, our own community of faith is also changing and this can felt at the front doors of our parishes – in the variety of people we now encounter with different situations, questions and expectations than in the past. Moving from those who no longer engage with us to those who are still present in our churches, there is no longer a ‘cookie cutter Catholic profile’ if there ever was one. Many of the only-affiliated Catholics can be found in our sacramental programs. Many self-identifying Catholics do not believe in God at all but send their children to our Catholic schools in any case, and many more would pick and mix among various traditions – Eastern meditation over here, the occasional Easter Vigil over there.

Moving from those who no longer engage with us to those who are still present in our churches, there is no longer a ‘cookie cutter Catholic profile’ if there ever was one. Many of the only-affiliated Catholics can be found in our sacramental programs. Many self-identifying Catholics do not believe in God at all but send their children to our Catholic schools in any case, and many more would pick and mix among various traditions – Eastern meditation over here, the occasional Easter Vigil over there. What is the upshot of this complexity for our outreach and accompaniment? Prior to any proclamation of the Church being heard, today’s missionary outlook will begin with building trust and authentic personal relationships (from which consequent invitations and participation might then come about).

What is the upshot of this complexity for our outreach and accompaniment? Prior to any proclamation of the Church being heard, today’s missionary outlook will begin with building trust and authentic personal relationships (from which consequent invitations and participation might then come about). To make this opportunity concrete and practical, the outreach of St Paul, perhaps the greatest evangeliser in the history of the Church after Jesus himself, can be a resource for our thinking on this ‘art of accompaniment’.

To make this opportunity concrete and practical, the outreach of St Paul, perhaps the greatest evangeliser in the history of the Church after Jesus himself, can be a resource for our thinking on this ‘art of accompaniment’. When we consider how many people receive the sacraments in our Church, whether the sacraments of initiation or each weekend, and how many come out the other side as disciples on mission sharing faith with others, we can see the need for accompaniment to support that journey. We have learnt that the sacraments simply won’t ‘take care of it’, that discipleship needs the support of relationships via a process such as Alpha that builds trust and encourages sharing in faith.

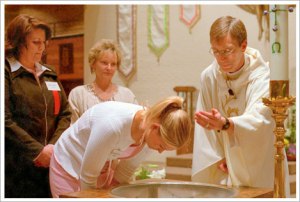

When we consider how many people receive the sacraments in our Church, whether the sacraments of initiation or each weekend, and how many come out the other side as disciples on mission sharing faith with others, we can see the need for accompaniment to support that journey. We have learnt that the sacraments simply won’t ‘take care of it’, that discipleship needs the support of relationships via a process such as Alpha that builds trust and encourages sharing in faith. On the 24 November, 1999, on a drizzly Wednesday evening, I was baptised in a parish in the north-western suburbs of Sydney. Heralding from a family of Buddhist and Taoist heritage, I entered the Church at the age of twenty, gathered with a priest, sponsor, fellow catechumens and a mixed group of close friends, mostly of no religious background. A small but powerful group had accompanied me through the process of initiation and I was fully conscious and grateful for the fact that in God and this community I had been granted something which I would spend the rest of my life learning to be faithful to, learning to enter into, learning to trust.

On the 24 November, 1999, on a drizzly Wednesday evening, I was baptised in a parish in the north-western suburbs of Sydney. Heralding from a family of Buddhist and Taoist heritage, I entered the Church at the age of twenty, gathered with a priest, sponsor, fellow catechumens and a mixed group of close friends, mostly of no religious background. A small but powerful group had accompanied me through the process of initiation and I was fully conscious and grateful for the fact that in God and this community I had been granted something which I would spend the rest of my life learning to be faithful to, learning to enter into, learning to trust. Reflecting on the Australian Church, I would concur that the central challenge for parish life is this: we are caught between a call and desire for renewal and the weight of our own church culture towards maintaining the status quo. In this moment which cries out for new apostolic zeal, we can feel bound by layers of expectation that demand the continuation of the old even while new forms of parish life and mission long for expression.

Reflecting on the Australian Church, I would concur that the central challenge for parish life is this: we are caught between a call and desire for renewal and the weight of our own church culture towards maintaining the status quo. In this moment which cries out for new apostolic zeal, we can feel bound by layers of expectation that demand the continuation of the old even while new forms of parish life and mission long for expression. Fundamentally we are called to be a Church of the Great Commission. This is our vision, the ‘northern star’ guiding our resolve. “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:19). As it has been pointed out, in our Catholic Church we have certainly learnt to “go” and can claim a presence at all corners of the earth. We “baptise” and confirm relentlessly. We “teach” and catechise great numbers in our schools and sacramental programs. However, our ability as Church to “make disciples” remains in question, as raised by the pastoral realities for the Australian Church we have explored.

Fundamentally we are called to be a Church of the Great Commission. This is our vision, the ‘northern star’ guiding our resolve. “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:19). As it has been pointed out, in our Catholic Church we have certainly learnt to “go” and can claim a presence at all corners of the earth. We “baptise” and confirm relentlessly. We “teach” and catechise great numbers in our schools and sacramental programs. However, our ability as Church to “make disciples” remains in question, as raised by the pastoral realities for the Australian Church we have explored. When we communicate a vision of the parish, how we seek to respond to God in this context, in this time, in this local community, when we can articulate a vision of the kinds of spiritual growth we are seeking to raise up in our people, this passionate purpose becomes the heartbeat or pulse of a parish. Conveniently, and not incidentally, a renewed vision provides the case for change.

When we communicate a vision of the parish, how we seek to respond to God in this context, in this time, in this local community, when we can articulate a vision of the kinds of spiritual growth we are seeking to raise up in our people, this passionate purpose becomes the heartbeat or pulse of a parish. Conveniently, and not incidentally, a renewed vision provides the case for change. It is worth noting that when a parish makes a commitment to a clear vision of personal discipleship and spiritual community, presenting this before its people, other good things begin to flow. With a vision pointing the parish beyond its own concerns and circumstance, the parish can begin to move from a culture that engages people to build up the Church to become a Church that builds up people.

It is worth noting that when a parish makes a commitment to a clear vision of personal discipleship and spiritual community, presenting this before its people, other good things begin to flow. With a vision pointing the parish beyond its own concerns and circumstance, the parish can begin to move from a culture that engages people to build up the Church to become a Church that builds up people. First of all, at the heart of evangelising communities is the proclamation of the Good News, specifically the kergyma which is the basic truths of our Christian faith. This word kerygma, or keryssein in Greek, may not be very familiar to us but it in fact appears in the New Testament some nine times, and refers to the very heart of the Gospel, the core message of the Christian faith that all believers are called to believe and proclaim.

First of all, at the heart of evangelising communities is the proclamation of the Good News, specifically the kergyma which is the basic truths of our Christian faith. This word kerygma, or keryssein in Greek, may not be very familiar to us but it in fact appears in the New Testament some nine times, and refers to the very heart of the Gospel, the core message of the Christian faith that all believers are called to believe and proclaim. The heart of evangelisation is to announce who Jesus is, the Son of God, the Word made flesh, the man who is God, who died for our sins and was raised on the third day. It is to announce the Good News of the Risen Christ who is with us even now and opens up for us the way to life without end. Evangelising parishes proclaim Jesus’ ascension, his seating at the right hand of the Father as King, and his sending forth of the Holy Spirit. It is this Spirit which reveals Christ and even enables us to say ‘Jesus is Lord’ and it is this Spirit who empowers the Church, who empowers us, to be faithful to Christ’s mission in our own lives and in this moment of the world’s history. Finally, this Good News of Christ calls us to conversion, to repent and believe in this Gospel, calling for a change of life in the light of what God has done and is doing in Jesus Christ whose life we share by baptism, the anointing of the Holy Spirit, in communion with his mystical body, the Eucharist, and by our communion with His ecclesial body, the Church. In prioritising this proclamation, we seek to build up a culture in which Jesus is not swept into our parish story intermittently but our parishes and lives are swept into his.

The heart of evangelisation is to announce who Jesus is, the Son of God, the Word made flesh, the man who is God, who died for our sins and was raised on the third day. It is to announce the Good News of the Risen Christ who is with us even now and opens up for us the way to life without end. Evangelising parishes proclaim Jesus’ ascension, his seating at the right hand of the Father as King, and his sending forth of the Holy Spirit. It is this Spirit which reveals Christ and even enables us to say ‘Jesus is Lord’ and it is this Spirit who empowers the Church, who empowers us, to be faithful to Christ’s mission in our own lives and in this moment of the world’s history. Finally, this Good News of Christ calls us to conversion, to repent and believe in this Gospel, calling for a change of life in the light of what God has done and is doing in Jesus Christ whose life we share by baptism, the anointing of the Holy Spirit, in communion with his mystical body, the Eucharist, and by our communion with His ecclesial body, the Church. In prioritising this proclamation, we seek to build up a culture in which Jesus is not swept into our parish story intermittently but our parishes and lives are swept into his. However, the bold proclamation of Jesus’ name, life, promises, Kingdom and mystery, in itself is not sufficient for the growth of a missionary culture in our parishes. As a second foundation, evangelising parishes cultivate personal discipleship, create room and opportunity for a personal response to the Good News proclaimed. The call to be a disciple is a gift but it also involves a choice and personal decision that cannot be delegated to any other.

However, the bold proclamation of Jesus’ name, life, promises, Kingdom and mystery, in itself is not sufficient for the growth of a missionary culture in our parishes. As a second foundation, evangelising parishes cultivate personal discipleship, create room and opportunity for a personal response to the Good News proclaimed. The call to be a disciple is a gift but it also involves a choice and personal decision that cannot be delegated to any other. Bringing together these first principles of evangelising communities, we hear St John Paul II affirm, “Faith is born of preaching and every ecclesial community draws its origin and life from the personal response from every believer to that preaching”.

Bringing together these first principles of evangelising communities, we hear St John Paul II affirm, “Faith is born of preaching and every ecclesial community draws its origin and life from the personal response from every believer to that preaching”. Personal discipleship also calls for the nourishment of an ecclesial community of faith. Evangelising parishes create disciples in the midst of the Church.

Personal discipleship also calls for the nourishment of an ecclesial community of faith. Evangelising parishes create disciples in the midst of the Church. While our vision needs to be as large as the Kingdom, our implementation of that vision needs to begin small. With encouragement for us, it is worth noting that when large evangelical and Pentecostal communities are asked what they seek for their future it is to establish smaller, stable communities in the midst of a local neighbourhood, offering a consistency and intimacy of worship and local service in personal connection with the wider community. In other words, what many megachurches are seeking is a parish.

While our vision needs to be as large as the Kingdom, our implementation of that vision needs to begin small. With encouragement for us, it is worth noting that when large evangelical and Pentecostal communities are asked what they seek for their future it is to establish smaller, stable communities in the midst of a local neighbourhood, offering a consistency and intimacy of worship and local service in personal connection with the wider community. In other words, what many megachurches are seeking is a parish. Finally, we recognise that the proclamation of the Gospel, the call to personal discipleship and the life of the Christian community are not for their own sake but for the sake of the world. All that has gone before must bear fruit in our connection with others beyond our communities of faith, beyond the boundaries of the parish.

Finally, we recognise that the proclamation of the Gospel, the call to personal discipleship and the life of the Christian community are not for their own sake but for the sake of the world. All that has gone before must bear fruit in our connection with others beyond our communities of faith, beyond the boundaries of the parish. Indeed, it can be seen that these foundations encourage and direct our efforts in this Jubilee Year of Mercy, in which the tenderness and compassion of God calls for announcement. An evangelising community proclaims the mercy of God whose face is Jesus Christ, nurtures our people to know themselves as personally forgiven by God and brought into the freedom of a new life, offers the experience of forgiveness and compassion within the life of the Church, sacramentally and in the companionship of fellow Christians; and equips and emboldens the forgiven to ‘go out’ to share mercy with others who too await someone to pour oil on their wounds, who await the Good News given in Jesus Christ, who is the promise and presence of God’s mercy.

Indeed, it can be seen that these foundations encourage and direct our efforts in this Jubilee Year of Mercy, in which the tenderness and compassion of God calls for announcement. An evangelising community proclaims the mercy of God whose face is Jesus Christ, nurtures our people to know themselves as personally forgiven by God and brought into the freedom of a new life, offers the experience of forgiveness and compassion within the life of the Church, sacramentally and in the companionship of fellow Christians; and equips and emboldens the forgiven to ‘go out’ to share mercy with others who too await someone to pour oil on their wounds, who await the Good News given in Jesus Christ, who is the promise and presence of God’s mercy. We cannot change that of which we are not aware. We must name and face head on the present challenges for our culture as Australian parishes, parishes that I believe desire to be missionary and in their heart of hearts wish to receive the grace of God who still desires much for our parish life.

We cannot change that of which we are not aware. We must name and face head on the present challenges for our culture as Australian parishes, parishes that I believe desire to be missionary and in their heart of hearts wish to receive the grace of God who still desires much for our parish life. The past months have seen numerous developments in the life of the universal Church and the national scene. Without doubt the most significant development has been the release of Pope Francis’ post-synodal Apostolic Exhortation on the joy of love in the family,

The past months have seen numerous developments in the life of the universal Church and the national scene. Without doubt the most significant development has been the release of Pope Francis’ post-synodal Apostolic Exhortation on the joy of love in the family,  With a dose of the same reality it is worth noting that it takes time and resources for this form of evangelical outreach and familiarity with our flesh-and-blood brothers and sisters. It has always struck me that while Pope Francis’ constant refrain to ‘go forth’ is both attractive and true to the spirit of the Gospel, it does in fact take organisation and resources to set out on mission. Any parish that has more than one community within it knows that it is difficult to be outreaching when, in the words of Sherry Weddell, you are ‘literally besieged at HQ’.

With a dose of the same reality it is worth noting that it takes time and resources for this form of evangelical outreach and familiarity with our flesh-and-blood brothers and sisters. It has always struck me that while Pope Francis’ constant refrain to ‘go forth’ is both attractive and true to the spirit of the Gospel, it does in fact take organisation and resources to set out on mission. Any parish that has more than one community within it knows that it is difficult to be outreaching when, in the words of Sherry Weddell, you are ‘literally besieged at HQ’. Amoris Laetitia exhorts us to encourage the young to aspire to marriage and family life all the while fostering realistic expectations that prepare them for mature relationships that inevitably experience change through time. It speaks of the need for married couples to be open to the prospect of new life, to educate children in virtue and to foster their natural inclination towards goodness (AL 264). It speaks of inclusion and affirms the Gospel as a word spoken to all people in every circumstance as a source of hope. Pope Francis also offers practical ideas to encourage husbands and wives in their journey of constant growth, and urges parishes and faith communities to be bearers of comfort and consolation for those who await mercy, who seek oil for their wounds (AL 309-310).

Amoris Laetitia exhorts us to encourage the young to aspire to marriage and family life all the while fostering realistic expectations that prepare them for mature relationships that inevitably experience change through time. It speaks of the need for married couples to be open to the prospect of new life, to educate children in virtue and to foster their natural inclination towards goodness (AL 264). It speaks of inclusion and affirms the Gospel as a word spoken to all people in every circumstance as a source of hope. Pope Francis also offers practical ideas to encourage husbands and wives in their journey of constant growth, and urges parishes and faith communities to be bearers of comfort and consolation for those who await mercy, who seek oil for their wounds (AL 309-310). Workshops are also offered across the three days of the conference and will canvass a range of topics that speak to the lived situation and evangelical mission of parishes today. For convenience I’ve listed the full range of workshops below. They encompass everything from the liturgical and sacramental life of the parish, personal discipleship and the discernment of gifts, social media and communicating the Gospel to youth and young adults, to the response of parishes to the sexual abuse crisis, the need of supervision and self-care in ministry, strategies for forming evangelisation teams, responding to Amoris Laetitia through parish based marriage preparation, engaging the multicultural face of the Church and incarnating Pope Francis’ vision of poverty in the local community of faith.

Workshops are also offered across the three days of the conference and will canvass a range of topics that speak to the lived situation and evangelical mission of parishes today. For convenience I’ve listed the full range of workshops below. They encompass everything from the liturgical and sacramental life of the parish, personal discipleship and the discernment of gifts, social media and communicating the Gospel to youth and young adults, to the response of parishes to the sexual abuse crisis, the need of supervision and self-care in ministry, strategies for forming evangelisation teams, responding to Amoris Laetitia through parish based marriage preparation, engaging the multicultural face of the Church and incarnating Pope Francis’ vision of poverty in the local community of faith.