This week I was privileged to attend and present at the Great Grace Conference, an event hosted by the Archdiocese of Sydney to commemorate 50 years since the opening of the Second Vatican Council. The keynote address and workshops proved dynamic and engaged head on with the issues that confront the Church and its mission, including the challenge of modernity, the need to address the education of the laity, and issues of authority and power, among others. Thank you to the 100 or so participants who attended my own workshop over the past two days which focused on the theme of ‘co-responsibility’ and lay leadership in the Church.

This week I was privileged to attend and present at the Great Grace Conference, an event hosted by the Archdiocese of Sydney to commemorate 50 years since the opening of the Second Vatican Council. The keynote address and workshops proved dynamic and engaged head on with the issues that confront the Church and its mission, including the challenge of modernity, the need to address the education of the laity, and issues of authority and power, among others. Thank you to the 100 or so participants who attended my own workshop over the past two days which focused on the theme of ‘co-responsibility’ and lay leadership in the Church.

The conference dinner, held last night, brought together a remarkable mix of delegates, bishops, theologians and lay leaders in the Church. It was good to catch up with new and old friends, including Robert Tilley of the Catholic Institute of Sydney and the University of Notre Dame, Matthew Tan of Campion College, Byron and Francine Pirola of the Marriage Resource Centre in Zetland, an inspiring couple of the Neocatechumenal Way, and the UK’s Jack Valero of CatholicVoices (pictured), a bold and pioneering lay-led media initiative that began in 2010 and that has just established itself in Melbourne (I’ll be blogging more about this initiative in weeks to come). The conference concludes today with addresses from Tracey Rowland and Bishop Mark Coleridge. Next week takes me north to the Gold Coast for the National Pastoral Planners Network Conference where I’ll be presenting on strategic planning within church communities.

For now, here is a summary of my ‘Great Grace’ presentation on co-responsibility which may be of interest to laypersons, religious or clergy in service of the Church (for those who prefer to listen, an audio file of the live workshop is now available here):

Since the Second Vatican Council the concept of ‘collaboration’ has been the dominant framework through which the relationship of laity to the ministry of the clergy has been read. However, that began to change on 26 May, 2009, when Pope Benedict XVI, in an address to the Diocese of Rome, raised the term ‘co-responsibility’ as an appropriate hermeneutic through which to interpret the role of laypersons in the Church.

This concept of ‘co-responsibility’ has surfaced as an explicit theme of the Church’s self-understanding only in recent decades. Even then, the idea appears in outline, and occasionally, rather than in a fully elaborated or systematic manner. When it does appear, the primary contexts in which the term ‘co-responsibility’ is employed in the official documents of the Church include the relationship between local churches, the workings of the college of bishops, the bond between nations, and the relationship of the Church and Christians to civil society. The term appears in the Catechism of the Catholic Church only once, again in the context of the duties of Christians toward the common good (cf. CCC n.2240).

To my knowledge, the first magisterial application of the term ‘co-responsibility’ to the laity appears in John Paul II’s 1988 Apostolic Exhortation Christifideles Laici, Article 21:

The Church is directed and guided by the Holy Spirit, who lavishes diverse hierarchical and charismatic gifts on all the baptised, calling them to be, each in an individual way, active and coresponsible.

The third chapter of the exhortation makes clear the context of this common responsibility – it is for the Church’s mission in the world which includes witness and proclamation of their communion with Christ. The document gives sparse attention to the responsibilities of laity within the Church, more concerned as John Paul II was at the time with a perceived “‘clericalisation’ of the lay faithful” and associated violations of church law.

The term is repeated ten years later in John Paul II’s comments at General Audience on the Holy Spirit. Here he remarked, “[the laity’s] participation and co-responsibility in the life of the Christian community and the many forms of their apostolate and service in society give us reason, at the dawn of the third millennium, to await with hope a mature and fruitful ‘epiphany’ of the laity.” In this instance ‘co-responsibility’ is understood to embrace both the active contribution of laity within the Church’s life as well as their social mission beyond it.

The term is repeated ten years later in John Paul II’s comments at General Audience on the Holy Spirit. Here he remarked, “[the laity’s] participation and co-responsibility in the life of the Christian community and the many forms of their apostolate and service in society give us reason, at the dawn of the third millennium, to await with hope a mature and fruitful ‘epiphany’ of the laity.” In this instance ‘co-responsibility’ is understood to embrace both the active contribution of laity within the Church’s life as well as their social mission beyond it.

Taken together, these early references do not supply us with a fully elaborated theology of co-responsibility. However, they do express an increasing consciousness of the agency of laypersons in the world as well as some recognition of their involvement in the Church. Laypersons contribute in both spheres, ad intra and ad extra, through their Spirit-led witness and baptismal discipleship.

Benedict XVI’s interventions

It was on the 26 May, 2009, that the term ‘co-responsibility’ first appeared in the thought of Pope Benedict, in continuity with the outline offered by John Paul II but with an added, distinguishing element that raises the profile of the concept for the Church’s self-understanding. The occasion was the opening of the annual Ecclesial Convention of the Diocese of Rome. Expressing the need for renewed efforts for the formation of the whole Church, Benedict insisted on the need to improve pastoral structures,

. . . in such a way that the co-responsibility of all the members of the People of God in their entirety is gradually promoted, with respect for vocations and for the respective roles of the consecrated and of lay people. This demands a change in mindset, particularly concerning lay people. They must no longer be viewed as ‘collaborators’ of the clergy but truly recognised as ‘co-responsible’ for the Church’s being and action, thereby fostering the consolidation of a mature and committed laity.

It’s important to affirm that Benedict’s appeal for a new mentality and recognition of co-responsibility falls within the specific context of lay ministry in the Church, and not simply their involvement in worldly mission. In this statement, Benedict has in mind those “working hard in the parishes” who “form the core of the community that will act as a leaven for the others.” These ideas recur, almost verbatim, three years later in Benedict’s message to the International Forum of Catholic Action.

It’s important to affirm that Benedict’s appeal for a new mentality and recognition of co-responsibility falls within the specific context of lay ministry in the Church, and not simply their involvement in worldly mission. In this statement, Benedict has in mind those “working hard in the parishes” who “form the core of the community that will act as a leaven for the others.” These ideas recur, almost verbatim, three years later in Benedict’s message to the International Forum of Catholic Action.

While, again, no systematic theology of co-responsibility appears in Benedict’s thought, he has introduced a degree of specificity to the term by way of a significant negation. The co-responsibility of the laity is not to be interpreted as a ‘collaboration’ in church ministry fitting to clergy alone, and therefore not as derivative in nature, but as an integral and authentic participation, an ecclesial responsibility, that is proper to laypersons themselves. It is because this contribution of laypersons is real, legitimate and essential to the Church’s life that it is to be given practical support in the form of appropriate structures. The significance of this statement by Benedict is best appreciated in the light of previous statements of the magisterium on the role of the laity vis-à-vis the Church and ordained ministry.

The 1997 Instruction

Pope Benedict’s application of the term ‘co-responsibility’ to laypersons is particularly striking when read beside the 1997 instruction, issued by the Holy See some 15 years earlier, entitled “On Certain Questions Regarding Collaboration of the Lay Faithful in the Ministry of Priests.”

I singled out this document for it well represents the predominant thinking of the magisterium on the relation of the laity and ordained within the Church’s unity. The instruction sought to reinforce the essential difference between the clergy and laity in the light of a perceived blurring of the boundaries in ministry that risked “serious negative consequences” including damage to a “correct understanding of true ecclesial communion.” While the document affirms the common priesthood of all the baptised and sets the ministerial priesthood within that context, the Instruction nevertheless promotes what Richard Gaillerdetz describes as a “contrastive” or categorical theology of the laity.

Specifically, the Instruction defines laypersons from a hierarchiological perspective with their theological status determined by two points of contrast with the ordained – the first, the ultimately secular character of the lay vocation in contradistinction to the ‘spiritual’ concerns of the ordained, and, secondly, the ministry of the baptised is differentiated from the ministry of the ordained by “the sacred power” (sacra potestas) uniquely possessed by the latter. Indeed, as Gaillerdetz observes, the Vatican instruction suggests that the fullness of ministry resides, by virtue of this sacral power, with the ordained alone.

On the basis of these two theological presuppositions – the ascription of laity to the secular realm and the ‘fullness of ministry’ to the ordained – the activity of the laypersons within the Church is cast as a ‘collaboration’ in the ministry of the ordained without a positive or integrated theological basis of its own. It must be said that the absence of such a theology can be explained, in part, by the purpose of the Instruction – it is a corrective, disciplinary document that seeks to uphold, quite rightly, the unique charism of the ordained. Still, as the Australian theologian Richard Lennan observes,

While that concern is proper, [such] documents tend to provide little encouragement to further reflection on the meaning of baptism, the possibility of ‘ministry’ for the non-ordained as other than a response to an emergency or an exception, or the implications of church membership for witnessing to the gospel in the communion of the church, rather than simply ‘in the world.’

The apprehension or hesitancy of this early Vatican instruction toward the status of lay involvement in Church ministry makes the “change in mindset” advocated by Benedict all the more significant. If laypersons are to be viewed not simply as collaborators in a ministry that belongs to another, but genuinely co-responsible in ecclesial life, as Benedict avers, then renewed reflection is called for regarding the positive theological status of laypersons and of their service in the Church, one that stretches beyond the paradigm of ‘collaboration’ that has dominated the lay-clergy relation to date.

I find possibilities for this positive, more constructive, and less contrastive, approach of the laity in the documents of the Second Vatican Council itself. Here we identify sound ecclesiological bases for the form of co-responsibility endorsed by Pope Benedict, flowing from the idea of communion that underpins the Council’s thought.

The Church as Communion

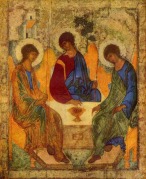

Returning to deeper biblical, patristic and liturgical sources clear of the juridical, extrinsicist tendencies of neoscholasticism, the communio ecclesiology of Vatican II expresses two primary insights. The first, a recovery of baptism as the primal sacrament of Christian life – prior to subsequent distinctions in charism, vocation or office; the second, a renewed appreciation of the Church as an icon of the Trinity, a relationship that promotes a mutuality of exchange between believers as an expression of the unity-in-diversity, the communion, that God is.

Returning to deeper biblical, patristic and liturgical sources clear of the juridical, extrinsicist tendencies of neoscholasticism, the communio ecclesiology of Vatican II expresses two primary insights. The first, a recovery of baptism as the primal sacrament of Christian life – prior to subsequent distinctions in charism, vocation or office; the second, a renewed appreciation of the Church as an icon of the Trinity, a relationship that promotes a mutuality of exchange between believers as an expression of the unity-in-diversity, the communion, that God is.

Lumen Gentium sought to ground all Christian vocations in what Kenan Osborne describes as a “common matrix” of baptismal faith for it is the entire people of God that are “by regeneration and anointing of the Holy Spirit… consecrated into a spiritual house and a holy priesthood,” “made one body with Christ, sharers in the priestly, prophetic and kingly functions of Christ” and so “share a common dignity from their rebirth in Christ, a true equality.” As Chapter 5 of Lumen Gentium avers, each member of the ecclesial body, baptised and confirmed in the Holy Spirit, shares “the same vocation to perfection” and all people are commissioned to the mission of the Church, not in a derivative way, but as Lumen Gentium 33 emphasises, they are called to this mission “by the Lord Himself”.

However, it is important to note that these gifts – baptismal regeneration, the tria munera of Christ, an equality in dignity and in the call to the heights of holiness – are ascribed to the entire christifideles, to all the faithful or People of God in their Christian vocation, and are not particular or distinguishing of the laity per se.

A Theology of the Laity

In seeking to identify a unique or distinctive element apropos the laity, scholars have pointed elsewhere in the conciliar documents, especially Lumen Gentium 31. This text directs attention to the distinct ‘secular character’ of the lay vocation in contrast to the ‘sacred’ ministry of the ordained: “to be secular is the special characteristic of the laity . . . the laity, by their very vocation, seek the kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and by ordering them according to the plan of God.”

The overall thrust of this and other documents leads the theologian Aurelie Hagstrom to conclude, “this secular character must be an essential part of any theology of the laity since it gives the specific element in any description of the laity’s identity and function. The peculiar character of the laity is not only a sociological fact about the laity, but also a theological datum.” In short, Hagstrom interprets these documents as raising the ‘secular character’ of the laity to the level of metaphysics, as belonging to the ontological status of the lay vocation as such. To be lay is to be immersed in the secular, or so it is proposed.

However, questions can be raised about the theological adequacy of such a presentation and its support in the breadth of the conciliar documents. For one, the subcommittee responsible for Lumen Gentium 31 – that section of the constitution that refers to the laity’s ‘secular character’ – did not intend this to stand as a reference to their ontology, as pertaining to the core of their being, but rather a ‘typological description’ of the situation of the laity, that is, a description of how lay men and women typically live, but not exclusively so (cf. the relatio of John Cardinal Wright). This original intent of the Council Fathers challenges a view that would limit the proper responsibility of laypersons to the external life of the Church, that is, ‘in the world’ alone.

However, questions can be raised about the theological adequacy of such a presentation and its support in the breadth of the conciliar documents. For one, the subcommittee responsible for Lumen Gentium 31 – that section of the constitution that refers to the laity’s ‘secular character’ – did not intend this to stand as a reference to their ontology, as pertaining to the core of their being, but rather a ‘typological description’ of the situation of the laity, that is, a description of how lay men and women typically live, but not exclusively so (cf. the relatio of John Cardinal Wright). This original intent of the Council Fathers challenges a view that would limit the proper responsibility of laypersons to the external life of the Church, that is, ‘in the world’ alone.

What is more, as Archbishop Bruno Forte points out, it is in fact the whole Church that the Council situates within the world as a leaven, in both Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes. Forte goes as far as to predicate ‘laicity’ not of a specific subset of the Church – that is, of its non-ordained members – but of the entire Church that serves the world as the “universal sacrament of salvation.” These conciliar perspectives challenge a conception of the Church in dichotomous terms, of clergy as the apolitical men of the Church; the laity as the less ecclesially committed, politically involved, ‘men of the world.’

The heart of the issue is that to define laypersons by an exclusively ‘secular character’ in contradistinction to the ‘sacred’, ecclesial ministry of clergy renders genuine co-responsibility within the life of the Church difficult if not problematic. As intimated, as long as laypersons are defined exclusively by an identity and function in ‘the world’ without taking into adequate account the reality of their witness within the Church, then their involvement in Church ministry can appear only a concession, an anomaly or even a usurpation of Church service that belongs properly and fully to the ordained alone. What is more, the definition of laity by a secular vocation stands in contrast to the pastoral reality of many thousands of laypeople engaged in church ministries which are obviously not secular. As Lennan concludes, the practice of Church ministry by lay men and women, the very reality of their co-responsibility within the contemporary Church, presently outstrips the theology and church policy regarding such matters. Lay ecclesial ministers such as ourselves are doing something in the Church that, ontologically speaking, appears incongruous for their ‘proper’ place has been read as being ‘in the world.’

Co-responsibility of Order and Charism

In moving beyond a “dividing-line model”, a hardened distinction of laity and clergy in isolated realms, it is helpful to consider the place given by the Council to the exercise of charisms within the Church’s mystery. Prior to the Council, the charismatic gifts of the Spirit were treated by theology primarily within the context of spirituality, as the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in the human soul of the individual believer. Considered extraordinary, transient and isolated in experience, the charisms of the Spirit were not integrated into a broader ecclesiological framework and so their relation to the sacraments, the life and mission of the Church remained largely overlooked.

In moving beyond a “dividing-line model”, a hardened distinction of laity and clergy in isolated realms, it is helpful to consider the place given by the Council to the exercise of charisms within the Church’s mystery. Prior to the Council, the charismatic gifts of the Spirit were treated by theology primarily within the context of spirituality, as the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in the human soul of the individual believer. Considered extraordinary, transient and isolated in experience, the charisms of the Spirit were not integrated into a broader ecclesiological framework and so their relation to the sacraments, the life and mission of the Church remained largely overlooked.

Building on the insights of Congar and other proponents of the ressourcement movement, Vatican II witnessed a recovery of the pneumatological foundations of the Church as presented in the writings of St Paul. A strong integration of the activity of the Spirit within the Church can be found in Lumen Gentium 12 with consequence for our theme of co-responsibility:

Building on the insights of Congar and other proponents of the ressourcement movement, Vatican II witnessed a recovery of the pneumatological foundations of the Church as presented in the writings of St Paul. A strong integration of the activity of the Spirit within the Church can be found in Lumen Gentium 12 with consequence for our theme of co-responsibility:

It is not only through the sacraments and the ministries of the Church that the Holy Spirit sanctifies and leads the people of God and enriches it with virtues, but, “allotting his gifts to everyone according as He wills,” He distributes special graces among the faithful of every rank. By these gifts, He makes them fit and ready to undertake the various tasks and offices which contribute toward the renewal and building up of the Church . . . Those who have charge over the Church should judge the genuineness and orderly use of these gifts and it is especially their office not indeed to extinguish the Spirit but to test all things and hold fast to that which is good.

While it is true that the Council is not here making an explicit link between charism and lay ministry per se, it does provide a foundation for understanding leadership by laypersons as something other than an exception, usurpation or offshoot of ordained ministry. In grounding the life of the Church in the work of the Spirit, the Spirit of Christ who ‘co-institutes’ the Church by the giving of gifts, the Council grounds all ecclesial activity, all “tasks and offices,” in the inseparable divine missions of both the Word and Spirit.

In the post-conciliar era it was Congar especially who would bring out the consequence of this unity of Christ and Spirit in the Church’s being for our understanding of ministry, including on the part of laity. In a 1972 article Congar takes issue with the largely ‘christomonist’ approach of the Church and ministry that had dominated Catholic ecclesiology since the age of high scholasticism. Congar critiques this linear and predominantly vertical perspective with acuity:

“Christ makes the hierarchy and the hierarchy makes the Church as a community of the faithful.” Such a scheme, even if it contains a part of the truth, presents inconveniences. At least in temporal priority it places the ministerial priest before and outside the community. Put into actuality, it would in fact reduce the building of the community to the action of the hierarchical ministry. Pastoral reality as well as the New Testament presses on us a much richer view. It is God, it is Christ who by his Holy Spirit does not cease building up his Church.

This richer view of the ‘building up’ of the Church’s life is indeed offered by Lumen Gentium 12 in its recognition of the Spirit’s bestowal of gifts on “the faithful of every rank,” on the entire christifideles. In renewing and building up the Church’s life, the Spirit is understood to operate throughout the entire community of God’s people, disclosing the Church as other than a pyramid whose passive base receives everything from the apex. The laity are indeed subjects of the Spirit’s action as persons of baptismal faith.

This appreciation of the entire Church as anointed by the Holy Spirit (LG 4), as entrusted with Scripture and tradition as Dei Verbum 10 insists, and with charisms of the Spirit that bear structural value for the Church, opens the way for recognition of lay ministry qua ministry for the life of the Church and its mission. In the light of a pneumatological ecclesiology, the activity of laity surfaces not as derivative, a mere collaboration in the ministry of another, but, as Benedict intimates, a genuine co-responsibility for the sake of communion with God in Christ by the Holy Spirit.

This appreciation of the entire Church as anointed by the Holy Spirit (LG 4), as entrusted with Scripture and tradition as Dei Verbum 10 insists, and with charisms of the Spirit that bear structural value for the Church, opens the way for recognition of lay ministry qua ministry for the life of the Church and its mission. In the light of a pneumatological ecclesiology, the activity of laity surfaces not as derivative, a mere collaboration in the ministry of another, but, as Benedict intimates, a genuine co-responsibility for the sake of communion with God in Christ by the Holy Spirit.

While affirming the Spirit’s guidance by “hierarchical and charismatic gifts”, the Council never successfully integrated these christological and pneumatological aspects of ecclesial life. They were simply placed side by side (cf. LG 4). As long as this integration of hierarchical order and charism remains lacking, the co-responsibility of laypersons within the Church risks being read by Catholics against, or even as a threat, to the unique charism of the ordained who act uniquely “in the person of Christ the Head.” In other words, there is a risk of distinguishing ordained ministries from lay ministries by associating Christ with the former and the Holy Spirit with the latter, a solution that is clearly inadequate. If the co-responsibility of the laity is to be fruitfully realised in the life of the Church, its future theology must hold charism and order, the missions of the Spirit and Christ, in unity without confusion or separation.

It has been suggested by Gaillardetz that the ordained priest, in that “discovery of gifts” described by the Council, directs and oversees the entire local community while, for the most part, the lay minister serves only within a particular area of ministry and does not exercise leadership of the community as a whole. To locate the charism of the ordained in the particular gift of leadership of the entire community upholds the principle that no matter how much pastoral work one does or how competent one becomes, the non-ordained person never ‘forms’ or ‘rules’ a community as a leader in the sense in which a cleric does. However, such an understanding of the unique charism of the ordained still permits recognition of other forms of Spirit-led leadership within the communion, under the oversight and with the encouragement of the ordained.

Though the integration of charism and order within the Council’s document was never achieved, there are within its letter foundations for an appreciation of ordained ministry not in opposition or above the Spirit-filled reality of the body but firmly within it as the apostolic principle of order and oversight of the local community. It is in recognising the Church’s constitution by both the missions of the Word and Spirit, in the ministry of the apostles and the Spirit given at Pentecost, that we can move toward a theology of co-responsibility that supports and extends the reality of both lay and ordained ministry vivifying the life of the contemporary Church.

As a final observation, it may well be the unfolding momentum of ‘the new evangelisation’ that offers the zeal and occasion for co-responsibility to be practiced with greater intensity in the mission and ministries of the Church. The new ecclesial movements, for one, have manifest the way in which the historical shape of the Church can be shaped by a renewed appreciation of the work of Christ and the Spirit, order and charism, clergy and the laity within a communion of faith, as endorsed by my conference paper.

As a final observation, it may well be the unfolding momentum of ‘the new evangelisation’ that offers the zeal and occasion for co-responsibility to be practiced with greater intensity in the mission and ministries of the Church. The new ecclesial movements, for one, have manifest the way in which the historical shape of the Church can be shaped by a renewed appreciation of the work of Christ and the Spirit, order and charism, clergy and the laity within a communion of faith, as endorsed by my conference paper.

Conclusion

‘Co-responsibility’ remains a developing concept that is to be understood in the context of the Church’s life as a communion. Tracing the appearance of the term within magisterial thought, I see the interventions of Pope Benedict XVI on the subject as particularly significant for the Church’s self-understanding. In differentiating ‘co-responsibility’ from mere ‘collaboration’, Benedict has prompted renewed thinking about the theological integrity of ministry by laypersons and the relationship of this growing service within the Church to divinely-given hierarchical order. It is through ongoing reflection on both the christological and Spirit-filled foundations of the Church, the missions of Christ and the Spirit in the ecclesial body, that the practice of co-responsibility, already growing at the level of pastoral practice, may be matched by a coherent theology that strengthens the contribution of laypersons in the decades to come.