On Friday 27 June 2025, the Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, I was privileged to speak at the inaugural Holy Shroud Conference at Liverpool Catholic Club. In preparing for the introductory address, I was drawn more deeply into the mystery of Christ’s Passion – not merely as historical event but as a living reality, imprinted not only on linen cloth but on our human situation today. The Shroud invites us to contemplate the face of the suffering Christ, to consider what it means that God chose to reveal Himself not in splendour, but in the vulnerability of a broken body out of love for us. I’m grateful to the organisers for their vision and hospitality, and to all those who came – not simply to learn more about a cloth, but to seek the One it points to: Jesus Christ, crucified and risen. May devotion to His Sacred Heart draw us ever closer to the love that knows no bounds.

First, let me thank you for your warm welcome and for gathering for this significant conference. It is an honour to be here with you tonight, and I bring greetings on behalf of the Archdiocese of Sydney.

I warmly welcome our esteemed speakers Fr Andrew Dalton, David Rolfe, William West and Dr Paul Morrissey, and congratulate the organising committee for bringing this opportunity to gather around the mystery of the Shroud in this Jubilee Year of Hope.

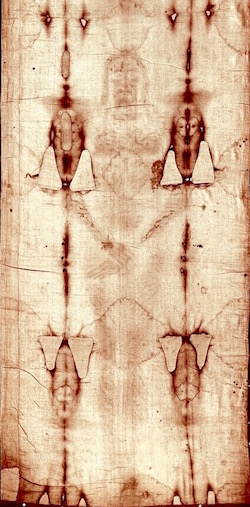

The topic before us, the Shroud of Turin, is one that has intrigued believers and non-believers alike for centuries. And in recent decades, it has become increasingly clear that the Shroud is not merely a religious curiosity. It is, in fact, one of the most extraordinary artefacts in human history. For many, it is a relic. For all of us, it is a mystery. And for those who seek truth, it can be a profound source of encounter with the Gospel.

We are living in an age that hungers for evidence, for the tangible, for something real, especially when it comes to faith. And it is here that the Shroud speaks powerfully.

Many now know that there is a great deal of scientific and historical evidence suggesting that the Shroud could not have been the work of a medieval forger, as claimed by the carbon dating results of 1988. In fact, the deeper we delve, the more difficult it becomes to dismiss the Shroud as merely a product of human hands.

What is often less well known is that many leaders within the Catholic Church have expressed not just interest, but belief in the authenticity of the Shroud. Among them are the past three popes – Pope John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis – each of whom made personal pilgrimages to venerate the Shroud.

Each of them stood before it not as sceptics, but as men of prayer and reverence, seeing in it a profound connection to the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

When Pope John Paul II visited the Shroud in 1980, he called it a “distinguished relic linked to the mystery of our redemption”. Eighteen years later, after the carbon dating controversy, he returned, this time thanking God for what he called “this unique gift”. That is no small statement. No pope would thank the Lord for a forgery.

More than that, John Paul II called us to gaze upon the Shroud with what he described as “the believer’s loving attention and complete willingness to follow the Lord”. In those words, he gently redirected us – not to get lost in the science or the debate – but to encounter the One whose image we believe is preserved on that cloth.

Pope Benedict XVI went further, stating that the Shroud had “wrapped the remains of a crucified man in full correspondence with what the Gospels tell us of Jesus”. Pope Benedict, who was always precise with his language, offered here a clear rebuttal to the carbon dating claims.

Even Dr Michael Tite, the man who oversaw that 1988 testing, later admitted in a 2016 BBC interview that he had come to believe a real human body had indeed been wrapped in the Shroud.

Pope Francis made pilgrimage to the Shroud in 2015. He not only prayed before it. He reached up and touched it. With great reverence, he said: “In the face of the Man of the Shroud, we see the faces of many sick brothers and sisters… victims of war and violence, slavery and persecution”.

For Pope Francis, the Shroud was not just about the past. It is about Christ’s presence among the suffering of today. And so the Shroud remains a powerful sign of hope as it witnesses to Christ’s solidarity with all those who suffer, who carry heavy burdens of illness, poverty, war, and injustice. It speaks to them not only of Christ’s passion, but of His enduring compassion – a reminder that they are not alone in their pain.

The late Pope concluded, saying: “By means of the Holy Shroud, the unique and supreme Word of God comes to us: Love made man… the merciful love of God who has taken upon himself all the evil of the world to free us from its power”. That is the evangelical heart of the Shroud. It is a silent sermon, a visual Gospel, a testimony in linen to the mystery of divine mercy.

In the context of this new pontificate, one cannot fail to recognise the providential continuity in Pope Leo XIV’s choice of name — Leo — which echoes that of his venerable predecessor, Pope Leo XIII, who in his own time zealously fostered devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus. This resonance serves as a quiet reminder that the Church’s memory is long, and that the Lord continues to speak to every age through signs both old and ever new.

Other Church leaders in our day have also drawn attention to the Shroud’s powerful witness. Just this past Easter, Bishop Robert Barron reflected in his Easter Sunday homily on the burial cloths mentioned in the Gospel of John. He called them “strange and wonderful cloths” and said they “opened the door to faith long ago”, and may well do the same today. Rather than referring to the Shroud as a mere “icon”, Bishop Barron described it as a relic, “one that is venerated as the cloth the disciples Peter and John saw on Easter Sunday morning”.

He is not alone. Popular priests such as Fr Mike Schmitz and Fr Andrew Dalton, who we are blessed to have as a speaker at this very conference, have powerfully and effectively evangelised through their engagement with the Shroud, especially among younger Catholics.

But perhaps most remarkable is the Shroud’s impact beyond the Church. Over the years, it has impressed and even converted many non-believers – atheists, agnostics, and sceptics who were drawn into a journey of faith by what they encountered in the scientific and spiritual mystery of the Shroud. It has spoken, too, to Protestants and Jewish seekers. Some have testified that their belief in God was rekindled through their encounter with the Shroud and the sense of the supernatural it evokes.

This brings me to what I believe is the Shroud’s most urgent and timely gift: its power to evangelise.

The Shroud is not just a matter of interest for scholars or theologians. It is something ordinary Catholics, young and old, can share in conversations with friends, colleagues, even strangers. It opens the door to a conversation not only about Christ’s suffering, but about His love, about His sacrifice, about the reality of the Resurrection.

And in a world that is increasingly sceptical of faith, increasingly disengaged from tradition, the Shroud is a bridge. It offers people a reason to pause, to question, to wonder.

It invites them to consider: Could this really be the burial cloth of Jesus? And if it is, what does that mean for my life?

After all, we live in an age in which so many do not believe in God, and yet so many still miss Him – a time when people chase progress without presence, and in which a Shroud, paradoxically, unveils something about life: a mystery that speaks to us, a silence that invites us to respond, a hiddenness that in Christ reveals us to ourselves, as sons and daughters of the crucified Son of God.

So, this evening, as we begin our conference, I encourage each of you not only to listen and learn, but to reflect on how you might carry this message forward. How the Shroud might be part of your own call to evangelise – to bear witness to a love that left its mark not only on human history, but on a simple linen cloth that continues to confound, inspire, and convert.

Thank you for your commitment to this mission. May the Man of the Shroud draw us ever closer to His heart.