I’m often asked the question: “What does it take to renew a parish?” My response is typically this – it is not merely a matter of filling the calendar with events. It is not achieved through a rebrand, a new logo, or an enhanced social media presence. It does not come from establishing additional committees. Nor is it simply a matter of rearranging the furniture, updating the website, or launching another fundraising initiative. While each of these efforts may have their rightful place, on their own, they are insufficient to bring about true renewal – one that is grounded in mission and evangelisation.

In experience, the renewal of parish life does not come about by addition, but rather by return. By “return,” I do not mean a reactionary traditionalism, but a re-discovery of Christ – a re-encounter with Him and a re-expression of His life in the heart of our community.

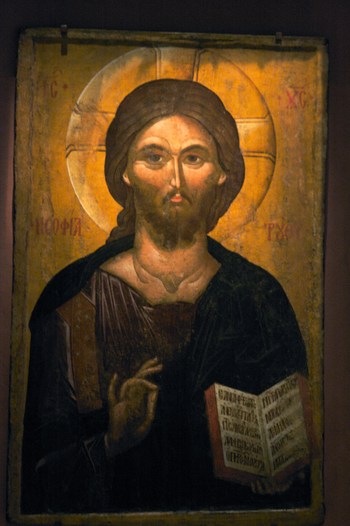

Renewal for the Catholic parish, as wisely observed by Fr James Mallon, looks much less like adding ornaments to a dying tree and much more like returning to its roots and nourishing them back to life. Pope Benedict XVI called for this decisive return when he defined our faith not as a philosophy or a moral code, but an encounter with a person, Jesus Christ, who gives our life “a new horizon and a decisive direction” (Deus Caritas Est 1).

This encounter is not an optional addition to the Christian life. It is its very essence. It must shape everything – how we worship, how we lead, how we form and disciple our people, and how we live out Christ’s mission in the world.

When Christ is truly at the centre, this encounter does not remain a private devotion but can shape the culture of the entire community. Culture, more than any program or plan, is where faith becomes visible, credible and contagious.

As it is often said today, culture is not a mission statement nor what is printed in the parish volunteer handbook. It is the lived atmosphere of a parish. Culture is found in the conversations in the car park, the tone of the preacher, at the front doors of the parish foyer, the unspoken assumptions behind every “we’ve always done it this way.” It is what people experience, not just what we intend.

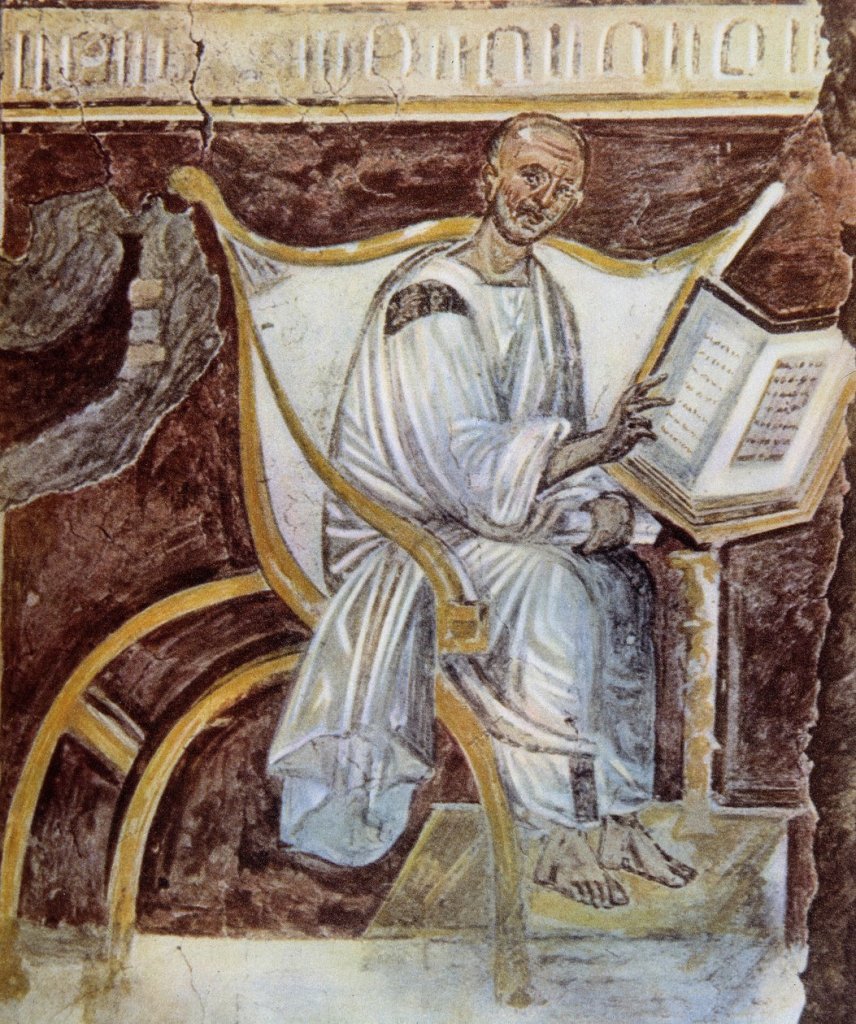

The Acts of the Apostles paints an evocative image of Christian culture embodied and alive: “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers… and day by day the Lord added to their number” (Acts 2:42–47). This was not a policy or program. It was a living expression of shared values – Christ-centred, generous, prayerful and missionary. Culture was not a by-product but the very soil in which evangelisation took root and the Gospel spread to the very ends of the world.

Then as now, renewal in our parishes does not begin with more ministries or events. We are privileged in Sydney to host many excellent opportunities – conferences, programs, international speakers, and gatherings where people can learn, reflect and be better equipped for mission. But these initiatives are always offered with a clear understanding that the roots of parish renewal lie much closer to home. Unless parish life is receptive, vibrant, and missionary, even the best events will not bear lasting fruit. No event or initiative can replace the power of a parish alive with faith, hope, and love at its core.

True renewal begins with local leadership committed to reshaping the culture of each parish – from passive attendance to personal calling, from spectatorship to discipleship, from the questions “What do I get from here?” or “What time or energy do I have to give?” to the deeper call: “What does Christ ask of me?”. If the culture of our parishes does not change, then over time, nothing else will. That is how vital the parish is to the life and future of the Church.

It is important to recognise that even the most intentional parish culture cannot endure without clarity. Clarity necessitates a well-defined purpose, a consistent message, and unified leadership exercised by both clergy and laity, whose collaborative stewardship is essential for faithfully guiding the parish deeper into Christ’s life and mission.

It can mean the difference between aimlessly running in circles, trapped in the rut of routine parish life with little spiritual fruit, and boldly guiding a parish and its people into a renewed encounter with Christ and a committed mission to share His love.

We can see this in the contrast of the Tower of Babel to the Upper Room at Pentecost. At Babel, confusion reigned and mission stalled. At Pentecost, the Holy Spirit bestowed clarity and conviction, coming like a mighty wind that filled and shook the house, and transformed many voices into one unified message and shared mission.

It is significant to recognise that this clarity neither narrowed the Church’s mission nor made the Apostles rigid or close-minded. Rather, clarity of vision propelled their mission boldly into the waiting world, enabling them to adapt and persevere amid countless challenges.

Clarity in parish life means knowing the purpose for which we exist. It means letting the essential mission given by Christ – making disciples – shape our priorities, budgets, preaching, events and even what we say “no” to. Clarity emerges not from constant activity and frenetic busyness but from deep conviction and intentional leadership. When parish leaders lack clarity, energy is scattered and vision begins to fade. When clarity is present, people are freed to focus on what matters most: helping others encounter Jesus Christ and walk with Him as missionary disciples.

For this culture and for this clarity, there is a fundamental call to conversion of heart, of habits and in parish leadership. This begins not with mere action but with the surrender of faith. Leadership without conversion becomes performance or image management. In the same way, ministry without prayer loses its foundation and becomes sterile, or reduced to mere maintenance, or worse, quiet neglect.

One story that has always struck me as instructive for parish renewal is that of Nehemiah. Before rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem, Nehemiah prayed, fasted and wept. His leadership emerged from the furnace of dependence on God and only then did he build something enduring, even in the face of resistance and the suspicion of others. Like Nehemiah, parish leaders must be “cupbearers of the Lord”, stewarding not just tasks but spiritual vision and communal growth.

If the vision of the parish is to be a community called by God, gathered around Christ in Word and Eucharist, and sent forth in the power of the Holy Spirit, then this vision must be woven into every conversation, every homily, every ministry, and every decision. Parishes do not drift naturally toward missionary vitality. They drift toward comfort, maintenance, and the familiar.

Too often, a parish calls people forward not for mission, but for the survival of its own structures as Pope Francis was only too keen to point out. Such a community might summon people forward to ministries, tasks, and functions for which there is never enough help. People are engaged to “fill the gaps”, and with this deficiency mindset of managed decline, the parish’s best energy is spent maintaining systems that bear little fruit.

However, the Church is not meant to merely survive and Christ deserves more than maintenance. The Church is called to proclaim, to disciple, to bear fruit that will last (Jn 15:16). Christ deserves more than our leftovers. What He calls forth is not self-preservation or resignation, but the transformation of lives in Him.

The question is no longer whether this kind of renewal is possible. We’ve seen it – in communities here in Sydney and in parishes across the world. The real question is whether we are willing to undergo the kind of interior conversion and communal commitment that such renewal demands. It is a question of surrender and of sustained resolve. Are we prepared to lead differently, live differently, and love differently to become the Church Christ calls us to be?

The Church of tomorrow is being shaped by the choices we make today, by leaders who keep the “main thing” the main thing: Jesus Christ as truly good news for every human heart. We must continue to cultivate parishes where the culture reflects Christ, where clarity shapes our vision, and where conversion is not a one-time event but the ongoing heartbeat of parish renewal. This remains our vision in Sydney. Only this kind of Church, anchored in Christ, led by the Spirit, and formed through prayerful conviction, will have the power to truly transform lives.