It was a privilege to present a workshop at the Australian Catholic Youth Ministry Convention 2018, held in the Diocese of Parramatta this past weekend. It was inspiring to be with youth ministers and leaders who are shaping the Church through their witness and initiative, from all sectors of the Church in Australia. Below is a summary of the workshop shared and I hope it’s of interest and encouragement in the ongoing work of renewal as we anticipate next month’s Synod on Youth.

This  workshop will extend the theme of ‘missionary discipleship’ to consider how youth ministry can support young people to move and grow from participation in youth ministry to exercise their discipleship as adults in broader parish and community life. If youth ministry gathers for the purpose of sending out, how can our ministries best prepare young people for that future? One of the claims of this workshop is that if we can identify the issues of our moment, and we know the destination at which we want to arrive, then this will shape the steps we can take to get there. If our purpose is sending young people out into mission, into the full life of the Church and world, then how does our youth ministry best prepare them for that future?

workshop will extend the theme of ‘missionary discipleship’ to consider how youth ministry can support young people to move and grow from participation in youth ministry to exercise their discipleship as adults in broader parish and community life. If youth ministry gathers for the purpose of sending out, how can our ministries best prepare young people for that future? One of the claims of this workshop is that if we can identify the issues of our moment, and we know the destination at which we want to arrive, then this will shape the steps we can take to get there. If our purpose is sending young people out into mission, into the full life of the Church and world, then how does our youth ministry best prepare them for that future?

The Discipleship Dilemma

As Pope Francis encourages, it is important to begin with a frank assessment of where we are as Church because “realities are more important than ideas” (EG 231-233; LS 110, 201). We cannot grow by holding the door closed against reality. A renewed future begins on the basis of the present. When we reflect on how best to lead young people into adult discipleship, we could reasonably ask how well our entire Church leads and makes disciples of all its members.

We know that the Church is called by God to work towards the transformation of the world so that it reflects more and more of God’s Kingdom or God’s reign. This Kingdom comes about when people encounter Jesus, surrender, and make the decision to follow – when they become his disciples and go out to transform the world. However, if this is the purpose of the Church, bringing about the Kingdom and making and forming disciples, we have to admit that we are not bearing the fruit we would like to see. More and more of our people, both young and old, continue to disengage from the Church, and we acknowledge the confronting reality that in the current climate some will question if the Church has anything worthwhile to say or be less inclined to be explicit in their faith. Another challenge presents itself in our parishes. If we were to measure how many of the hundreds who receive the sacraments in our local parishes each year, pass through our sacramental life in initiation or from week to week, and emerge on the other side as missionary disciples, the result would be less than ideal. There is something amiss. Where is the fruit?

The reasons for our decline have become clearer over time. At heart, we have a discipleship dilemma. When it comes to a personal and active relationship with Jesus Christ, many Catholic communities have taken a pastoral approach that assumes the sacraments will simply ‘take care of it’ and that is simply not true. We have neglected our duty to awaken in each person that active and personal faith, that fertile soil, in which the grace of the sacraments can actually take root and bear fruit. To make the point, “baptisms, confessions, weddings, funerals, daily devotions, anointing, and adoration. It’s all good stuff, it’s how some Catholics grow spiritually. For others, it’s what they do instead of grow . . . For certain, the sacraments give us grace to put us in right relationship to God and his life in our soul, nourishing and strengthening us for our discipleship walk. But they’re not mean to replace it’”.[1] This is not to discount the centrality of the sacraments or to deny the place that devotions have in the Catholic life. But it is to say that people can be ‘sacramentalised’ without being evangelised. It is entirely possible to undertake a routine of religious custom and practice without a personal and responsive relationship to Jesus Christ.

The sacraments do indeed give us the capacity to believe – the virtue of faith – but without a personal ‘yes’ – an act of faith – it remains a ‘bound’ sacrament. Like a car full of fuel, if we never turn the key or press the accelerator, we do not move forwards and we are not changed. Our personal ‘yes’ is the spark which enables grace to bear real fruit in our lives. Writing of youth, John Paul II recognised this same dilemma, “A certain number of children baptised in infancy come for catechesis in the parish without receiving any other initiation into the faith and still without any explicit personal attachment to Jesus Christ; they only have the capacity to believe placed within them by Baptism and the presence of the Holy Spirit.”[2] We know that children and youth who have no explicit personal attachment to Jesus are likely to grow up to be adults with no personal attachment to Jesus, unless that relationship is introduced into their life through a process of evangelisation.

Our Catholic tradition affirms this very point – that the sacraments do not replace personal discipleship. Vatican II’s Sacrosanctum Concilium affirms that the sacraments presume a living faith amidst its people.[3] The Catechism of the Catholic Church tells us explicitly, “The sacred liturgy does not exhaust the entire activity of the Church: it must be preceded by evangelisation, faith, and conversion”.[4] The Second Vatican Council and the Catechism affirm the Eucharist as “the source and summit of the Christian life” (CCC 1324). When there is no Christian life, no trace or intention of Christian living, then in fact the Eucharist can be neither source nor summit of anything. Outside of the context of discipleship, the Eucharist can be reduced to an object of piety or mere consumption rather than a relationship that invites a Jesus-shaped life. Finally, Jesus himself gives us a Great Commission “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, [and then] baptise them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teach them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:19). We could say that the mission of the Church is not sacraments but disciples which the sacraments nourish. Unless people become disciples, the grace of the sacraments bears little fruit.

It is important to recognise that the young people in our care are already being shaped and formed by this culture of sacramental routine, marked by a lack of fruit and the gentle decline in living faith. To render this concrete, take the typical experience of a Church-attending youth. They might intuit from the pews that parish participation is declining (in fact, the total percentage of Mass attendance nears single digits across the country) and will gain a quick sense that very few of their peers attend Eucharist on any given weekend (about 5% of all aged 20-34 in fact).[5] They would know too well that few of their peers’ families are engaging with the Church, and they may not witness many or any new people coming into the Church at Easter (perhaps a handful each year, while dozens more walk out the back door at the same time). They might recognise that while many receive the sacraments they are not seeing the fruit of a change in lives, that there is something missing and church attendance doesn’t seem to make a great difference to people’s lives. They may hear a little about the Church, history, or even morality, but they may not hear much about Jesus or hear the story of Jesus’ life shared clearly (when preaching is poor or misaligned). They may never have witnessed an adult actually speak about how Jesus has changed their life or heard conversations among adults about Jesus (even though a culture of testimony lies at the heart of evangelisation, for consumer churches have preferences while missionary churches have stories of how Jesus has changed their life).

These are some of the basic experiences that young people may encounter in our faith communities. The risk is unless we are casting in our youth ministries an alternative vision for what adult discipleship looks like, our young people may not receive any other image of adult life in the Church and therefore be given little sense of a positive future. We have a deep sense that we are called to do more than lead young people into adult communities which show little life in themselves, repeat the outcomes or trends of decline we have experienced in past generations of Catholics in Australia.

If our adult community and the cultures of our parish communities have forgotten what ‘normal’ looks like, it is the prophetic role of youth ministry to recover a new norm by equipping young people to move from a faith that can be customary, inherited or barren to a faith which is intentional (not routine), personal (not merely the faith of my family but a faith truly my own), and fruitful (there are signs of concrete change in our life for discipleship is not an invisible phenomenon, it shows up in the pigment of our life). In looking at change from one culture to another, we note that it is not the cultural norm in Catholicism to even talk about Jesus, let alone his fruit or work in our life, and those who do are viewed as Protestant or a spiritual pretender.[6] We have forgotten what ‘normal’ looks like. Youth ministry can play a part in the gradual transformation of our Church culture, to place again a full and living discipleship to Jesus before young people, as the heart of what we do and who we are as Catholics.

We can consider the radical difference that youth ministry can make to the Church in this way – via the analogy of what makes a good school. We know that a lack of academic opportunity is passed on or transmitted from generation to generation and, as such, students from lower socio-economic backgrounds often do not perform as well as they could. However, some education systems (e.g. those in Shanghai and Korea but sadly not Australia) are able to lift these students well beyond their statistical likelihood of poor academic performance, enabling these young people to perform and excel at their full potential. Quite simply, good schools and teachers make a difference to the capacities and lives of their students. They can break the cycle of ignorance and disadvantage. In a similar way, we know that ignorance of the faith is passed on or transmitted from generation to generation, and that many of our people start their journey in the Church ‘disadvantaged’ by low religious literacy and low or no commitment to practice, including little enthusiasm for sacrificial discipleship or evangelisation of others. The aim of good parishes, schools and youth ministries is to lift people out of this religious rut and support them to grow in faith and discipleship above and beyond what their background might have equipped them for. If our communities are not equipping our young people for living discipleship, then perhaps it is our ministry that can make that difference. I wanted to start on the note of realism, with recognition of what we are sending our young people into, and a note of possibility of what youth ministry can do within the wider life of the Church and within a Catholic culture desperately in need of renewal.

Youth Ministry

Having named the discipleship dilemma in our wider Church, which impacts upon the future of young people in faith, we now turn to focus on the reality of youth ministry itself. What is the status quo or state of play in youth ministry today?

Some of the significant dilemmas we are confronting include a ‘drop off’ after a time in parish groups and during senior high school among youth. For young adults, the decline in participation can set in during the post-school years, in the years of university or the first years of work. We sense that many of those aged between 25-35 years are being lost to the Church’s life, and other young adults are left hungry and even look back to youth ministry to serve their needs after the age of 30. These real experiences expose a gap and need in our approach to youth ministry, with many asking, ‘to whom shall we go?’ As it stands, we see young adults graduate from youth groups, a small number emerge as spiritual entrepreneurs who have learned to fend for themselves, but many more become ‘lost’ or drifters within the life of the Church, and a silent majority of young adults, I fear, slip into the routine culture of the crowd or disappear from the life of the Church altogether. Young people will continue to leave the scene as groups dwindle and their social support fades in the Church, or they will ‘hang on’ to their youth experience for dear life and risk a sort of extended adolescence well into their thirties with the crisis of vocation that can accompany being lost. If people are feeling lost in their thirties, it is saying something about how we are or are not preparing young people in youth ministry for a lasting life of faith.

The Causes of Decline

What is it about youth ministries that can lead to the disengaged, unchurched and the lost? We have an opportunity to make a real difference with those we do encounter but we do not always quite hit the mark. Some of the limited outcomes we see in youth ministry can be related to the purpose for which they exist. Take these four examples, keeping in view that a problem well recognised is a problem half solved.

The social but not spiritual group. There will be youth groups that exist for their own social value and are perhaps more an exercise in demography rather than discipleship. The parish decides it is good to have a youth group or a school a new youth team of sorts, so they establish one and the community feels better for it because we are ‘doing something for youth’. In short, the group exists for its own sake rather than for others. It will inevitably become insular, cliquey and decline, rather than outreach and grow, operating from a consumption model (‘this group is about me’) rather than of outreach and apostolic intent. It can often be marked by a sense that if the group gets any larger they will lose their intimate sense of community. The members do not intentionally reject ‘new’ people, but their present relationships are so intimate that any newcomer can find it difficult to break into the group. Especially when small, these social groups can stunt personal growth rather than enable it, especially if a group is populated with young people with nowhere else to go. Of course, the Church is there for all people, most especially the poor in spirit and circumstance, but if youth groups or ministries are not as broad and refective as the surrounding community, it can serve as a refuge from the world rather than a launching pad for faith in the world.

Youth groups as a retention strategy. Sometimes groups can be formed or used as a remedy for the declining participation that takes place after the sacraments of initiation. After all, who doesn’t want to ‘keep the kids in church’. However, such group can have short futures as they will tend to focus on behaviour modification (turning up to Mass or staying in Church) rather than discipleship. What they do not realise is that when people become disciples – encounter Jesus, surrender their life to him, and make the decision to follow – they will go to Mass for the rest of their lives. We want people to fall in love, not merely fall in line. If a group is simply about retaining members, then youth leaders will need to constantly come up with new and gimmicky ideas to retain the current membership and ‘get them to Mass’ but never address the deeper ‘why’ that might sustain them for a lifetime of faith. Groups that are established or see themselves merely as a retention strategy aim for the short-term but are unable to take the longer view with the usual outcomes of steady decline as the novelties and techniques wear thin.

Youth ministry as catechesis. Another reality for youth ministry can be an exclusive focus on catechesis, on teaching young people the facts about Catholicism and learning content, even when young people may not have a relationship with Jesus (i.e. have not even been evangelised). When we think about the word ‘catechesis’ itself (κατήχησις) as it is found in the Gospel of Luke 1:4, 1 Corinthians 14:19 and Galatians 6:6 it means ‘to sound out’ or to ‘echo the teaching’. It is like standing at the entrance of a cave and speaking out and hearing a voice coming back. When we catechise young people, we are speaking into their lives. We are giving them faith and knowledge, and what we seek is for that faith and knowledge to resound back, echo back upon its reception. However, the only way we can hear an echo is if there is a cave, if there is a space to speak into. If we were to run out and shout at a brick wall, we are not going to hear an echo as there is no space to absorb and reverberate what is being shared. So, we need to bring people to a living and transformative encounter with Jesus first, to create space within them for the Gospel, before we can teach or learning can take place. It has been pointed out that in the history of our Church, we have so often confused indifference with ignorance. People often do not care, have no space for the Gospel, but we think they simply do not have enough information so we catechise them and yet we wonder why nothing is sinking in. It is like trying to plant seeds in concrete! If we continue to prepare and form young people in this same way – only catechise – then we will continue to arrive at the same results, with young people unprepared for a life of adult faith because we never evangelised, made and formed them as disciples.

Finally, youth ministry as a process of duplicating groups. One other response to the disengagement of young adults from the Church we can see is the simple duplication of the same youth groups and structures for an older cohort. However, the question then is ‘where should that process end?’ Should we have groups for those aged 30-35 and then for those 40-45 years of age or would we presume and prepare at some stage their integration and leadership in the wider Christian community?

We can see how some of the outcomes we are seeing in youth ministry with drop off or disengagement can be shaped by our starting points or understanding of what our purpose is as a ministry of the Church. All these four models or tendencies within youth ministries miss the mark, which is to make disciples who have encountered, surrendered and made the decision of faith. More positively, if we do make disciples of young people, they will naturally yearn to be with other Christians (be social), they will live their life within the Church, even through thick and thin, because of their personal relationship and love of Jesus (they will be retained), they will be open to learning (catechesis) and be sustained as adults in older years with a genuine heart for Christ (experience spiritual conviction, not simply repeat behaviours). However, if we begin with other starting points, we cannot expect to see the fruit we are called to bring to life.

Toward Renewal

Moving forwards then, how might we make and form disciples, so they can graduate from youth groups and experience genuine personal and spiritual change that will last? Jesus invites us, through his command to Peter, “to go and bear fruit that will last” (John 15:16). As shared earlier, I think our youth ministries can create a new path and be the change and difference that our wider Church so sorely needs.

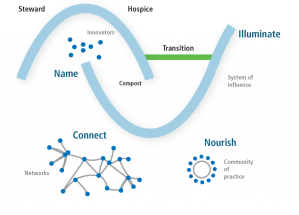

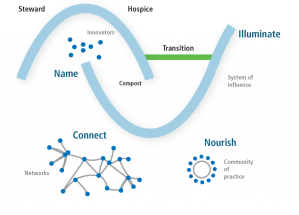

We can see the difference youth ministries can be through what are called ‘Berkana loops’ which are simply a helpful companion in thinking through how change and growth come about.

When our youth ministries first get off the ground, we can enjoy growth and excitement as the life cycle begins. Our group can be thriving, and we are good stewards of this growth. However, at some point things in the group can begin to plateau, perhaps because we have become comfortable and established, or we are not gaining new members or enthusiasm begins to wane. We start to lose significance or momentum.

When things begin to decline, we enter a ‘hospice’ stage where we are caring for a group in decline. However, as things plateau, there are some who see what is going on and what is not working, they might see what is lacking through a sort of ‘holy discontent’, and can begin to ask questions about impact or methods, and they begin to think of a new way forward. They recognise that God’s mission is greater than our existing methods which are no longer bearing fruit as they might have at other times.

These innovators might feel isolated in their hunger for a new form of engaging young people until they connect with others who have discerned a similar hunger, need or possibility. Now a network of innovators emerges, and they begin connecting on a regular basis. They begin to take action and become a community of practice, as a new possibility continues to emerge and build. With time, space, resources, expertise or by building new skills a new reality and a new way of mission or outreach comes into being.

There will be some stewards of youth ministry who are called to ‘sit by the bedside’ and accompany youth groups to their end, perhaps because that is their charism or they do not quite muster the courage or imagination to change and adapt. Sometimes youth ministries do have their time and naturally come to their end. However, others might make the transition from an old to a new way of doing things which has been led and created by others. When we recognise what is missing in our wider Church and some of our youth ministry – a focus on discipleship – we can put those missing pieces in place with the young people in our care.

Raising Discipleship

So, how do we raise discipleship among new generations that will last into adulthood? Firstly, our own witness is essential. Our witness demonstrates what a new life in Christ looks like. If our own Church attendance and involvement in the life of the Church does make a difference in how we live, if we are actively learning a style of life steered by love, it provokes a response from the young people in our care and opens a path of curiosity, trust and dialogue.

It is important to underscore that it is not our youth programs that make disciples; it is disciples that make disciples. Courses, programs and materials are only as good as the people using them. Without disciples to run a program, they do little good. It is not that we do not appreciate good materials. However, as it has been said, in the history of the life of the Church we did not have good materials. We had people. We had disciples making disciples. Right now, due to a lack of disciples, we may need the materials as a kind of crutch but we need to be careful about allowing them to replace the relationships.

Our witness enables us to then credibly proclaim the Gospel, most centrally the kerygma which is the kernel of the Gospel that centres on Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. The kerygma refers to the basic truths of our Christian faith, the core message of the Christian faith to which all believers are called to assent and proclaim. Pope Paul VI declared, “There is no true evangelisation if the name, the teaching, the life, the promises, the Kingdom and the mystery of Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of God are not proclaimed”.[7] This is the kerygma. It is explicit and focused entirely on the person and saving message of Jesus Christ.

We have to tell this Great Story of Jesus if it is to be known. The heart of evangelisation in youth ministry is to announce who Jesus is, the Son of God, the Word made flesh, the man who is God, who died for our sins and was raised on the third day. It is to announce the Good News of the Risen Christ who is with us even now and opens up for us the way to life without end. Evangelising youth ministries proclaim Jesus’ ascension, his seating at the right hand of the Father as King, and his sending forth of the Holy Spirit. It is this Spirit which reveals Christ and even enables us to say ‘Jesus is Lord’ and it is this Spirit who empowers the Church, who empowers us, to be faithful to Christ’s mission in our own lives and in this moment of the world’s history. Ultimately, this Good News of Christ calls us to conversion, to repent and believe in this Gospel, calling for a change of life in the light of what God has done and is doing in Jesus Christ whose life we share by baptism, the anointing of the Holy Spirit, in communion with his mystical body in the Eucharist, and by our communion with His body, the Church.

We are called to bring young people to a transformational encounter with this Jesus, connecting his story with our life. Again, the power of our initial witness and then proclamation has a lot to do with our own transformation and encounter, our own conversion. Pope Francis notes, “A true missionary who never ceases to be a disciple, knows that Jesus walks with him, speaks to him, breathes with him, works with him. He senses Jesus alive with him, in the midst of his missionary enterprise… a person who is not convinced, enthusiastic, certain, and in love, will convince nobody”.[8] Hence, how are you telling the Great Story of Jesus in your ministry? We are called to share that Jesus’ mission was to bring about the Kingdom marked by abundance and that we, as his disciples, are called to do the same, bringing the world’s limitation to divine possibility, that is, to the fullness of life (John 10:10).

This is the kind of vision of discipleship we need to proclaim. The American author Sherry Weddell remarks that if nobody talks about what discipleship looks like, it becomes difficult for people to begin to walk on that road, “Unfortunately, most of us are not spiritual geniuses. If nobody around us ever talks about a given idea, we are no more likely to think of it spontaneously than we are to suddenly invent a new primary colour. To the extent we don’t talk explicitly with one another about discipleship, we make it very, very difficult for most Catholics to think about discipleship”.[9] It is difficult to believe in and live something that you have never heard anyone talk about or that you have seen very others, including older adults, live with joy. We must witness, tell the story of Jesus, and cast a vision of discipleship, of personal and spiritual change, as the ultimate fruit of all other gifts in the Church, including the sacraments and our ministries to the young.[10]

In casting that vision of discipleship we need to be committed and resolute because other understandings of youth ministry can be cast at us (e.g. youth ministry as the social group, the retention strategy, as catechesis or duplication). A great example of resoluteness in holding and living our vision is illustrated by SouthWest Airlines, a low-fare carrier in the U.S. that seeks to ‘democratise’ air travel. Humour is a core dimension of its vision (e.g. the on-board announcements, “Would someone put out the cat?”; “We will be serving dinner on this flight and dessert if everyone behaves themselves”). Nevertheless, the airline received a complaint about their style, from a customer who regarded it as unprofessional and improper for an airline company. On receipt of a complaint, we could probably assume the line of management that would follow (i.e. a letter comes into the central office, the director of customer service rings the branch manager and asks them to ‘tone it down’, before sending the customer some form of compensation e.g. a meal voucher or a free fare). However, Southwest Airlines did not do this. Instead, they sent this customer a short letter with just four words on it. It read: “We will miss you.” The airline does not compromise on its vision and stands by the fact that there are many other uninteresting and boring airlines that customers are well free to choose. So it is with us in our vision of discipleship – it is the very reason for which the entire Church exists, is non-negotiable, and is that image of life that will support the young to live their faith into adulthood, as they come to know themselves as witnesses to the reign or Kingdom of God.

A further step in accompaniment of the young must be to assist them to actually live in that direction. Take for example the rich young man who encounters Jesus. It is not enough for this young man to meet Jesus, but he is then invited to sell all that he has – in other words to start living in the right direction (Mk 10:17-31). We can learn this principle also from the gift of marriage. We can encounter another person, get to know them, and even develop a personal relationship with them. However, to be married someone has to make the decision to ask and a decision to say ‘yes’. It is the same for discipleship – we are called to assist young people to make decisions that set them in the right direction. After all, we are all going somewhere, whether we know it or not, and will arrive at a destination in life.

The road that we are currently on will lead to a destination, and we generally do not drift in good directions. There are physical paths that lead to predictable locations, and physical roads and physical highways that lead to predictable destinations. There is a dietary path that leads to a predictably physical destination. There are financial paths that lead to predictable financial destinations. There are relationship paths that lead to predictable relational destinations. In fact, parents often ask their children questions about who they are dating for this reason. They are not so interested in whether their child is happy in the relationship now (though they hope they are). They are more interested where that relationship will take their child, whether that relationship will take them in the right direction.

As you know for the young people in your care they can in fact be completely content and satisfied and still be heading in the wrong direction. It is akin to driving on the road. You can be perfectly content in the car but become lost and you never know the precise moment you became lost, otherwise you would not have taken that turn. You can be a hundred metres past where you need to be and by the time you realise it, it is too late. It can cost you ten minutes. In life, if you are content but headed in the wrong direction and don’t know it, it can cost you years. It is often our nature to think ‘now is now’ and ‘later is later’ but everything we do has a consequence and will be connected. Biblically speaking, we reap what we sow. All our steps lead somewhere, so what we do everyday matters more than what we do once in a while when it comes to our ultimate direction in life.

The poet Gerard Manly Hopkins developed this term ‘inscape’ for the individual structure of a living being (like a tree or a leaf), an inner structure which results from the history of this being, an inner design made by the tree through its life in the way it has responded to life. We are much the same, our life is a work of art and all the good and the bad, conflicts and sufferings, troubles and happiness in our life all add up to something, all produce this inner structure, and this is what we are judged on, our encounter with Jesus and the direction that we chose to live. We are judged not on small incidentals (eating meat on Fridays) but rather the whole structure of our life – all that we wanted to do, tried to do, our relationships. This all adds up to our identity which God knows. Hence the value of youth ministers as spiritual guides who can help the next generation to be in touch with the whole direction and meaning of their life as a whole, what it is all adding up to and to encourage them to develop in this direction and not another.

The poet Gerard Manly Hopkins developed this term ‘inscape’ for the individual structure of a living being (like a tree or a leaf), an inner structure which results from the history of this being, an inner design made by the tree through its life in the way it has responded to life. We are much the same, our life is a work of art and all the good and the bad, conflicts and sufferings, troubles and happiness in our life all add up to something, all produce this inner structure, and this is what we are judged on, our encounter with Jesus and the direction that we chose to live. We are judged not on small incidentals (eating meat on Fridays) but rather the whole structure of our life – all that we wanted to do, tried to do, our relationships. This all adds up to our identity which God knows. Hence the value of youth ministers as spiritual guides who can help the next generation to be in touch with the whole direction and meaning of their life as a whole, what it is all adding up to and to encourage them to develop in this direction and not another.

We need, in fact, to develop an intentional culture of mentorship if young people are to grow and make decisions on the way to a lasting and adult faith. Why do young people need you as a mentor? Part of the reason is because experience is a rough teacher and it costs time. As shared by a Christian evangelist, Andy Stanley, ‘Perhaps you’ve heard someone make the argument that experience is the best teacher. That may be true, but that’s only half the truth. Experience is often a brutal teacher. Experience eats up your most valuable commodity: time. Learning from experience can eat up years. It can steal an entire stage of life. Experience can leave scars, inescapable memories, and regret. Sure, we all live and learn. But living and learning don’t erase regret. And regret is more than memory. It is more than cerebral. It’s emotional. Regret has the potential to create powerful emotions – emotions with the potential to drive a person right back to the behaviour that created the regret to begin with. If regret can be avoided, it should be’. Life will throw enough hardship at us by itself. We can avoid unnecessary pain and regret by learning from the experience of others. We need to reach back to those a stage of life behind us and make it easier for that next generation to encounter Christ and to live for him because people develop best when they see what their value being lived out in other Christians. We know hypocrisy discourages faith and good witness raises it up.

In creating that culture, I also want to invite youth ministers not to underestimate their capacity to be a spiritual mentor for others, regardless of their age or history. As a Carthusian monk once penned, our years of age tell us only this, “that the earth has gone around the sun so many times since I came into this world. That is the normal measure of what the world calls time.”[11] However, there is another ‘age’ which is measured by the time we have spent in the life of Christ, the spiritual growth and progress we have made in our time of faith. The mentorship of youth ministers for young people in their care honours our Christian faith as nothing less than a life being passed on, for our tradition of witness is ‘hand clasping hands stretching back in time until they hold the hand of Jesus who holds the hand of God’.[12]

The qualities youth leaders can develop as mentors to support and nourish the discipleship of the young are well spelt out by the preparatory document for the forthcoming Synod on Youth to be held in October 2018. It helpfully shares:

“The young people of the Pre-synodal Meeting accurately detail the profile of the mentor: ‘a faithful Christian who engages with the Church and the world; someone who constantly seeks holiness; is a confidant without judgement; actively listens to the needs of young people and responds in kind; is deeply loving and self-aware; acknowledges their limits and knows the joys and sorrows of the spiritual journey’. For young people, it is particularly important that mentors recognise their own humanity and fallibility: ‘Sometimes mentors are put on a pedestal, and when they fall, the devastation may impact young people’s abilities to continue to engage with the Church’. They also add that ‘mentors should not lead young people as passive followers, but walk alongside them, allowing them to be active participants in the journey. They should respect the freedom that comes with a young person’s process of discernment and equip them with tools to do so effectively. Mentors should believe wholeheartedly in a young person’s ability to participate in the life of the Church. They should nurture the seeds of faith in young people, without expecting to immediately see the fruits of the work of the Holy Spirit. This role is not and cannot be limited to priests and religious, but the laity should also be empowered to take on such a role. All such mentors should benefit from being well-formed, and engage in ongoing formation”.[13]

While it can appear that we are looking for ‘Jesus on a good day’, all of us can bring something of our imperfect selves and the treasure of our life and experiences of the world to those in our care. However, if we are going to support young people to healthily progress through youth groups and to become adult disciples, we will also need adult or older mentors in the lives of young people. As we shared, if a young person never sees or hears an adult talk about their relationship with Jesus, how would they know this relationship is even possible? As noted by Everett Fritz, we want young people to learn to participate in the world of adults, but our youth culture has largely removed adults from mentoring roles with teenagers. “As a result, teens are growing up in a peer-dominated culture. As they grow into adulthood, they have difficulty assimilating into the adult world and into the responsibilities and expectations that come with being an adult.”[14] While peer to peer ministry has its place, in clarifying our life direction, we should not only seek advice from people who share the same season of life, because it is akin to asking for directions of someone who has never been where you want to go.

We have a rich biblical tradition of older mentors investing in younger mentees including Moses and Joshua, Elijah and Elisha, Paul and Timothy and Titus, and Jesus and his disciples. Adults bring a unique blend of experiences, insights, conflict, choices, health challenges, convictions, and even failures and struggles to believe. Having adult mentors and witnesses in the midst of youth ministry, and a variety of adults, is essential if talk of discipleship and the Church is going to be meaningful in real-life ways. As it has been said, our faith is ever one generation away from its silence if it is not passed on, from one generation to the next.

Conclusion

How might we better prepare young people for adult discipleship in our age? We can begin to acknowledge the discipleship dilemma we are experiencing as a Church, seek to create and innovate a new way with others that learns from these limitations, provide a living witness to a life in Christ wholly given over and surrendered, proclaim the Great Story of Jesus, cast a vision of the discipleship he asks of us, accompany young people to live in that direction, and include mentors, both peers and adults, in the normal practice of youth ministry. I propose that it is these foundations, applied to local contexts, that can resource young people to live a Christian life beyond the confines of youth ministry, to grow into adult disciples and agents of renewal in our Church.

References:

[1] Fr Michael White and Tom Corcoran, Rebuilt: Awakening the Faithful, Reaching the Lost, Making Church Matter (Ave Maria Press: Notre Dame, Indiana, 2013), 77.

[2] John Paul II, Catechesi Tradendae 19.

[3] Vatican II, Sacrosanctum Concilium 59.

[4] Catechism of the Catholic Church #1072.

[5] Robert Dixon, Stephen Reid and Marilyn Chee, Mass Attendance in Australia: A Critical Moment. A Report Based on the National Count of Attendance, the National Church Life Survey and the Australian Census (Melbourne: ACBC Pastoral Research Office, 2013), 2-3.

[6] Cf. Sherry Weddell, Forming Intentional Disciples (Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington, Indiana, 2012), 63.

[7] Pope Paul VI, Evangelii Nuntiandi 22.

[8] Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium 266.

[9] Weddell, Forming Intentional Disciples, 56.

[10] A disciple can be defined as one who has encountered Jesus, surrendered their life, and made the decision to follow, or be understood by its expression as provided by Fr James Mallon, as one who has a personal relationship with Jesus, shares faith with others, is open to the gift of the Holy Spirit, has a daily prayer life, with commitment to Eucharist and Reconciliation, can pray spontaneously out loud when asked, and sees their life as a mission field. Cf. Fr James Mallon, Divine Renovation Guidebook: A Step-by-Step Manual for Transforming Your Parish (Novalis: Toronto, Ontario, 2016), 159.

[11] A Carthusian, They Speak by Silences (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1955), 38-9.

[12] John Shea, An Experience Named Spirit as cited in Robert A. Ludwig, Reconstructing Catholicism: For a New Generation (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2000), 61.

[13] Instrumentum Laboris for Synod 2018, 132.

[14] Everett Fritz, The Art of Forming Young Disciples: Why Youth Ministries Aren’t Working and What to Do About It (Sophia Institute Press: Manchester, New Hampshire, 2018), 46.

We celebrate the Ascension of Christ and approach the Feast of Pentecost in the light of the Resurrection. Christ is risen. Truly, He is risen!

We celebrate the Ascension of Christ and approach the Feast of Pentecost in the light of the Resurrection. Christ is risen. Truly, He is risen! As we learn from the Acts of the Apostles, it is the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, promised to them by Jesus at his Ascension, that marks a new chapter in the disciples’ faith.

As we learn from the Acts of the Apostles, it is the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, promised to them by Jesus at his Ascension, that marks a new chapter in the disciples’ faith. It happens that in these past months the experience of surrender has come to us. A global pandemic has left us dependent upon and yet strangely cautious of others, all at once. Individuals and entire communities are now vulnerable to a terrible scourge, originating on a distant horizon, that has brought life as we know it – in our homes, schools, workplaces and churches – to a collective and sudden halt. This global disruption is a striking reminder for us as Christians, and others besides, that we are not masters of our own world.

It happens that in these past months the experience of surrender has come to us. A global pandemic has left us dependent upon and yet strangely cautious of others, all at once. Individuals and entire communities are now vulnerable to a terrible scourge, originating on a distant horizon, that has brought life as we know it – in our homes, schools, workplaces and churches – to a collective and sudden halt. This global disruption is a striking reminder for us as Christians, and others besides, that we are not masters of our own world. As we pray and reflect on the role of the Holy Spirit in the world, we find this life-giving presence in the opening verses of the Hebrew Scriptures. Here we see the Spirit of God at the beginnings of creation as it “sweep[s] over the face of the waters” (Gen 1:2).

As we pray and reflect on the role of the Holy Spirit in the world, we find this life-giving presence in the opening verses of the Hebrew Scriptures. Here we see the Spirit of God at the beginnings of creation as it “sweep[s] over the face of the waters” (Gen 1:2). This spirit-filled history of salvation continues into the New Testament where the revelation of God comes to fulfilment in Jesus Christ. Jesus’ entire life unfolds under the sign of the Spirit.

This spirit-filled history of salvation continues into the New Testament where the revelation of God comes to fulfilment in Jesus Christ. Jesus’ entire life unfolds under the sign of the Spirit. This Spirit comes to each one of us as a gift but also as a challenge to the ongoing conversion of our heart and mind. As the source and giver of all holiness, we implore the Spirit to keep us in grace and remove those artificial obstacles, habits and ways of thinking that prevent us from living fully in and for Christ. As St Paul writes in the Letter to the Romans, our baptism in Christ calls us to live no longer by the flesh, by the material things or selfish desires of this world, but to live according to the Spirit (Rom 8:5). It is for this new life that the Spirit of God dwells in us, the very same Spirit that raised Jesus from the dead (Rom 8:11).

This Spirit comes to each one of us as a gift but also as a challenge to the ongoing conversion of our heart and mind. As the source and giver of all holiness, we implore the Spirit to keep us in grace and remove those artificial obstacles, habits and ways of thinking that prevent us from living fully in and for Christ. As St Paul writes in the Letter to the Romans, our baptism in Christ calls us to live no longer by the flesh, by the material things or selfish desires of this world, but to live according to the Spirit (Rom 8:5). It is for this new life that the Spirit of God dwells in us, the very same Spirit that raised Jesus from the dead (Rom 8:11). Of course, the fruits and gifts of the Holy Spirit are especially manifest in the saints. These ‘bright patterns of holiness’ remind us that Christian sanctity is not just an ideal or possibility but a reality in concrete persons and the concrete conditions of the world. This cloud of witnesses, these Christian exemplars, are models of holiness who have responded to the needs, challenges and opportunities of their time. These saints allowed themselves to be filled with the Spirit. In the pattern of Mary, “full of grace” the saints give birth or expression to Christ in the world.

Of course, the fruits and gifts of the Holy Spirit are especially manifest in the saints. These ‘bright patterns of holiness’ remind us that Christian sanctity is not just an ideal or possibility but a reality in concrete persons and the concrete conditions of the world. This cloud of witnesses, these Christian exemplars, are models of holiness who have responded to the needs, challenges and opportunities of their time. These saints allowed themselves to be filled with the Spirit. In the pattern of Mary, “full of grace” the saints give birth or expression to Christ in the world. The Church, as the third-century theologian St Hippolytus affirmed, is “the place where the Spirit flourishes”. The Church is the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit animating and bringing to life and holiness its members through the Word and sacraments, the ministry of the ordained (our bishops, priests and deacons), the various gifts and charisms of the faithful of every rank, the varieties of religious orders and ecclesial movements that express the Spirit’s power and anointing.

The Church, as the third-century theologian St Hippolytus affirmed, is “the place where the Spirit flourishes”. The Church is the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit animating and bringing to life and holiness its members through the Word and sacraments, the ministry of the ordained (our bishops, priests and deacons), the various gifts and charisms of the faithful of every rank, the varieties of religious orders and ecclesial movements that express the Spirit’s power and anointing. As the Feast of the Ascension brings us to reflect on our Christian pilgrimage in this world and to the next, we do not have a choice between God and the world. As Christians, we choose God by choosing the world as it really is in Him. We choose God by working toward the transformation of the world as disciples, empowered by the Holy Spirit who inspires true freedom and furthers God’s plan of salvation.

As the Feast of the Ascension brings us to reflect on our Christian pilgrimage in this world and to the next, we do not have a choice between God and the world. As Christians, we choose God by choosing the world as it really is in Him. We choose God by working toward the transformation of the world as disciples, empowered by the Holy Spirit who inspires true freedom and furthers God’s plan of salvation. In the wake of the worldwide spread of COVID-19 and the limitations it places on human interaction and activity, the ability for Catholics to physically gather for liturgy comes under increasing threat. It is worth noting as attendance at churches thins and may well be prohibited into the future in some jurisdictions, there may be an increased appreciation for something that that has been taken away by these circumstances. Once precautions surrounding the Mass are lifted many may return to our parishes, including those whose participation has been infrequent or irregular.

In the wake of the worldwide spread of COVID-19 and the limitations it places on human interaction and activity, the ability for Catholics to physically gather for liturgy comes under increasing threat. It is worth noting as attendance at churches thins and may well be prohibited into the future in some jurisdictions, there may be an increased appreciation for something that that has been taken away by these circumstances. Once precautions surrounding the Mass are lifted many may return to our parishes, including those whose participation has been infrequent or irregular. This includes for we Australians. While the number of marriages in our Church has declined sharply over the years, the number of families and children who continue to seek the Sacraments of Initiation in our parishes remain substantial, in their many thousands.

This includes for we Australians. While the number of marriages in our Church has declined sharply over the years, the number of families and children who continue to seek the Sacraments of Initiation in our parishes remain substantial, in their many thousands. So, what explains this phenomenon which sees thousands ‘sacramentalised’ but few appearing to be ‘evangelised’, that is, become intentional and life-long disciples of Jesus Christ? It cannot a deficiency of the sacraments in which we encounter the power and presence of Christ himself.

So, what explains this phenomenon which sees thousands ‘sacramentalised’ but few appearing to be ‘evangelised’, that is, become intentional and life-long disciples of Jesus Christ? It cannot a deficiency of the sacraments in which we encounter the power and presence of Christ himself. We know that reception of the sacraments can be treated as a mere social custom, a family tradition practiced without intention, or else sought for purposes other than itself. Whether it is driven by a desire for enrolment in Catholic schools, a bending to family pressure or social conformity, thousands continue to seek out sacraments in our parishes but often little else. Not only this, but the mixed motivations behind the demand for Baptism can be known, accepted or even encouraged by our silence on the matter. If this pattern persists, we risk nothing less than “a ritualism devoid of faith” (9).

We know that reception of the sacraments can be treated as a mere social custom, a family tradition practiced without intention, or else sought for purposes other than itself. Whether it is driven by a desire for enrolment in Catholic schools, a bending to family pressure or social conformity, thousands continue to seek out sacraments in our parishes but often little else. Not only this, but the mixed motivations behind the demand for Baptism can be known, accepted or even encouraged by our silence on the matter. If this pattern persists, we risk nothing less than “a ritualism devoid of faith” (9). Of course, this is not to say the efficacy of the sacraments depends on the one who receives. Baptism, for instance, confers a real “sacramental character” as God’s grace is truly given. But what baptism places within us is a capacity to believe. It cannot be a substitute for an active response, the ‘act of faith’ on the part of the graced subject. A sacrament can be valid but for it to be fruitful, it must be received in faith for “God makes the acceptance of this gift dependent on the cooperation of the recipients” (32). As St Augustine put it, God ‘did not will to save us without us’.

Of course, this is not to say the efficacy of the sacraments depends on the one who receives. Baptism, for instance, confers a real “sacramental character” as God’s grace is truly given. But what baptism places within us is a capacity to believe. It cannot be a substitute for an active response, the ‘act of faith’ on the part of the graced subject. A sacrament can be valid but for it to be fruitful, it must be received in faith for “God makes the acceptance of this gift dependent on the cooperation of the recipients” (32). As St Augustine put it, God ‘did not will to save us without us’. Underlining these reactions to the Plenary Council will be varying understandings of the Church itself and of the possibilities for reform. Contrasting ecclesiologies about the best way in which the Church can exercise its mission are certainly not new. Polarisation has been an increasing mark of Catholic exchange particularly since the Second Vatican Council and intensified in the ‘phase of disillusionment’ that followed. These divisions about the way forwards for the Church have been inflamed by the Church’s waning influence in the Australian community and the search for a response to a loss of credibility and public voice over past decades which risks for the Church what Greg Sheridan has described as ‘complete strategic irrelevance’ (‘Christian churches drifting too far from the marketplace of ideas’, The Australian, 4/6/2016). The resulting ecclesial tensions and ideological rifts will inevitably spill over to shape people’s expectations and engagement with the Plenary Council as an initiative of the Church, explicitly geared as it is towards reform.

Underlining these reactions to the Plenary Council will be varying understandings of the Church itself and of the possibilities for reform. Contrasting ecclesiologies about the best way in which the Church can exercise its mission are certainly not new. Polarisation has been an increasing mark of Catholic exchange particularly since the Second Vatican Council and intensified in the ‘phase of disillusionment’ that followed. These divisions about the way forwards for the Church have been inflamed by the Church’s waning influence in the Australian community and the search for a response to a loss of credibility and public voice over past decades which risks for the Church what Greg Sheridan has described as ‘complete strategic irrelevance’ (‘Christian churches drifting too far from the marketplace of ideas’, The Australian, 4/6/2016). The resulting ecclesial tensions and ideological rifts will inevitably spill over to shape people’s expectations and engagement with the Plenary Council as an initiative of the Church, explicitly geared as it is towards reform. Towards this end what the Plenary Council will do and is doing is generating a significant, even if for some unsettling, conversation about the way in which the Church can best practice its mission in Christ into the future. A Plenary Council can, for example, pass legislation regulating how doctrine is to be taught, how worship is to be regulated and how governance is to occur in practice. It is to these matters that diverse input is needed for the benefit of the Church’s missionary mandate.

Towards this end what the Plenary Council will do and is doing is generating a significant, even if for some unsettling, conversation about the way in which the Church can best practice its mission in Christ into the future. A Plenary Council can, for example, pass legislation regulating how doctrine is to be taught, how worship is to be regulated and how governance is to occur in practice. It is to these matters that diverse input is needed for the benefit of the Church’s missionary mandate. Under present canon law, the decisions of the Council are made by bishops by nature of their episcopal ordination as successors of the Apostles. However, it would be mistaken to read this exercise of authority as an isolated act for in casting their deliberative vote the bishops are required to be attentive to the counsel of the people in their dioceses and at the Council sessions themselves. The magisterium must sense with the Church as a whole where the Spirit’s inspiration is leading. Lay delegates at the Council will have a consultative vote, namely a real vote which will be written and tallied and is to be considered seriously by those with a deliberative vote. So it is that the bishops are obliged to make decisions on the basis of their careful discernment of the work of the Holy Spirit in the minds and hearts of the People of God, recognising that the sense of the faith of the faithful – what is known as the sensus fidelium – is a source of the Church’s life and learning as it pilgrims through history.

Under present canon law, the decisions of the Council are made by bishops by nature of their episcopal ordination as successors of the Apostles. However, it would be mistaken to read this exercise of authority as an isolated act for in casting their deliberative vote the bishops are required to be attentive to the counsel of the people in their dioceses and at the Council sessions themselves. The magisterium must sense with the Church as a whole where the Spirit’s inspiration is leading. Lay delegates at the Council will have a consultative vote, namely a real vote which will be written and tallied and is to be considered seriously by those with a deliberative vote. So it is that the bishops are obliged to make decisions on the basis of their careful discernment of the work of the Holy Spirit in the minds and hearts of the People of God, recognising that the sense of the faith of the faithful – what is known as the sensus fidelium – is a source of the Church’s life and learning as it pilgrims through history. Nor does it represent the intent of the listening process underway until Lent 2019. The thousands upon thousands of submissions and voices they represent will shape the major themes that will constitute the agenda of the Plenary Council. Naturally in the abundance of data received will be conflicting interpretations of what has been revealed in Jesus, the Scriptures and our Catholic tradition and varied proposals on how best to incarnate the Gospel in our present situation and our future. This interpretive maelstrom is not a new experience for the Church (think of the disputes of Saints Peter and Paul, and the divergences of the Pauline and Johannine communities).

Nor does it represent the intent of the listening process underway until Lent 2019. The thousands upon thousands of submissions and voices they represent will shape the major themes that will constitute the agenda of the Plenary Council. Naturally in the abundance of data received will be conflicting interpretations of what has been revealed in Jesus, the Scriptures and our Catholic tradition and varied proposals on how best to incarnate the Gospel in our present situation and our future. This interpretive maelstrom is not a new experience for the Church (think of the disputes of Saints Peter and Paul, and the divergences of the Pauline and Johannine communities). workshop will extend the theme of ‘missionary discipleship’ to consider how youth ministry can support young people to move and grow from participation in youth ministry to exercise their discipleship as adults in broader parish and community life. If youth ministry gathers for the purpose of sending out, how can our ministries best prepare young people for that future? One of the claims of this workshop is that if we can identify the issues of our moment, and we know the destination at which we want to arrive, then this will shape the steps we can take to get there. If our purpose is sending young people out into mission, into the full life of the Church and world, then how does our youth ministry best prepare them for that future?

workshop will extend the theme of ‘missionary discipleship’ to consider how youth ministry can support young people to move and grow from participation in youth ministry to exercise their discipleship as adults in broader parish and community life. If youth ministry gathers for the purpose of sending out, how can our ministries best prepare young people for that future? One of the claims of this workshop is that if we can identify the issues of our moment, and we know the destination at which we want to arrive, then this will shape the steps we can take to get there. If our purpose is sending young people out into mission, into the full life of the Church and world, then how does our youth ministry best prepare them for that future?

The poet Gerard Manly Hopkins developed this term ‘inscape’ for the individual structure of a living being (like a tree or a leaf), an inner structure which results from the history of this being, an inner design made by the tree through its life in the way it has responded to life. We are much the same, our life is a work of art and all the good and the bad, conflicts and sufferings, troubles and happiness in our life all add up to something, all produce this inner structure, and this is what we are judged on, our encounter with Jesus and the direction that we chose to live. We are judged not on small incidentals (eating meat on Fridays) but rather the whole structure of our life – all that we wanted to do, tried to do, our relationships. This all adds up to our identity which God knows. Hence the value of youth ministers as spiritual guides who can help the next generation to be in touch with the whole direction and meaning of their life as a whole, what it is all adding up to and to encourage them to develop in this direction and not another.

The poet Gerard Manly Hopkins developed this term ‘inscape’ for the individual structure of a living being (like a tree or a leaf), an inner structure which results from the history of this being, an inner design made by the tree through its life in the way it has responded to life. We are much the same, our life is a work of art and all the good and the bad, conflicts and sufferings, troubles and happiness in our life all add up to something, all produce this inner structure, and this is what we are judged on, our encounter with Jesus and the direction that we chose to live. We are judged not on small incidentals (eating meat on Fridays) but rather the whole structure of our life – all that we wanted to do, tried to do, our relationships. This all adds up to our identity which God knows. Hence the value of youth ministers as spiritual guides who can help the next generation to be in touch with the whole direction and meaning of their life as a whole, what it is all adding up to and to encourage them to develop in this direction and not another. I was grateful to be part of a workshop this week hosted by the Australian Catholic Youth Council in North Sydney. It drew together a select group of parish and diocesan youth leaders in conversation with Australia’s delegates for the October Synod on youth, Archbishop Anthony Fisher OP and Bishop Mark Edwards OMI, as well as Archbishop Comensoli.

I was grateful to be part of a workshop this week hosted by the Australian Catholic Youth Council in North Sydney. It drew together a select group of parish and diocesan youth leaders in conversation with Australia’s delegates for the October Synod on youth, Archbishop Anthony Fisher OP and Bishop Mark Edwards OMI, as well as Archbishop Comensoli. As the Church in Australia considers its future, it is imperative to understand the interactions and experiences that comprise young people’s lives for these provide the building blocks for renewed mission with and to young people. While the Catholic faith may today occupy less surface space in Australian culture, the rise of dedicated disciples within promises to bring new depths to our Christian living and cultural impact, and encourage the whole Church in its mission to the concrete people of each generation.

As the Church in Australia considers its future, it is imperative to understand the interactions and experiences that comprise young people’s lives for these provide the building blocks for renewed mission with and to young people. While the Catholic faith may today occupy less surface space in Australian culture, the rise of dedicated disciples within promises to bring new depths to our Christian living and cultural impact, and encourage the whole Church in its mission to the concrete people of each generation. Challengingly, among Australian Catholic youth the influence of Church or religious leaders in their key decisions and directions is thin, identified as significant by just 11% of those surveyed and aged between 16-18 years. This meek influence might be explained by a lack of personal relationship amongst some clergy and young people, the broader collapse of the Church’s credibility in the light of the sexual abuse crisis, and the real struggle of Church leaders to listen or ‘hold’ the questions that young people are asking of the Church. On this score, young Australian Catholics rated their experience of being listened at a modest 5.9 out of 10.

Challengingly, among Australian Catholic youth the influence of Church or religious leaders in their key decisions and directions is thin, identified as significant by just 11% of those surveyed and aged between 16-18 years. This meek influence might be explained by a lack of personal relationship amongst some clergy and young people, the broader collapse of the Church’s credibility in the light of the sexual abuse crisis, and the real struggle of Church leaders to listen or ‘hold’ the questions that young people are asking of the Church. On this score, young Australian Catholics rated their experience of being listened at a modest 5.9 out of 10. Positively, when Australian youth were asked how the Church can be of help to them, the responses actively invited our communities to provide guidance, to assist and counsel young people in their anxieties, personal challenges, understanding of sexuality and relationship issues.

Positively, when Australian youth were asked how the Church can be of help to them, the responses actively invited our communities to provide guidance, to assist and counsel young people in their anxieties, personal challenges, understanding of sexuality and relationship issues. Frustratingly for many, the accompaniment urgently desired by young Australian Catholics and urged by Pope Francis cannot be found neatly contained within a package or program. It demands in fact an entire culture of ecclesial life in which discernment is a norm and in regular evidence. When genuine discernment is not practiced in our sacramental programs, leading to fruitless reception, when RCIA processes teach people about Catholicism but neglect to train them to live as disciples, when parish pastoral councils and parish groups are more focused on ‘who will do it?’ rather than ‘where are we going?’, the offer of accompaniment to young people will appear more like false advertising than the expression of a community fully open to what God wants for the Church. The preparatory document for the Synod minces no words, “We cannot expect our offer of pastoral accompaniment towards vocational discernment to be credible to young people, unless we show that we are able to practice discernment in the ordinary life of the Church”.

Frustratingly for many, the accompaniment urgently desired by young Australian Catholics and urged by Pope Francis cannot be found neatly contained within a package or program. It demands in fact an entire culture of ecclesial life in which discernment is a norm and in regular evidence. When genuine discernment is not practiced in our sacramental programs, leading to fruitless reception, when RCIA processes teach people about Catholicism but neglect to train them to live as disciples, when parish pastoral councils and parish groups are more focused on ‘who will do it?’ rather than ‘where are we going?’, the offer of accompaniment to young people will appear more like false advertising than the expression of a community fully open to what God wants for the Church. The preparatory document for the Synod minces no words, “We cannot expect our offer of pastoral accompaniment towards vocational discernment to be credible to young people, unless we show that we are able to practice discernment in the ordinary life of the Church”. Held in Brisbane for the first time in its short history, Proclaim Conference 2018 gathered more than 600 participants from 12-14 July to discuss parish evangelisation with its theme drawn from John’s Gospel, “Make your home in me”. Keynote speakers over the three days included Archbishop Mark Coleridge, Cardinal John Dew from Wellington, Ron Huntley of the Divine Renovation network, Karolina Gunsser from Citipointe Church in Redcliffe, and Lana Turvey-Collins from the national facilitation team for the Plenary Council.

Held in Brisbane for the first time in its short history, Proclaim Conference 2018 gathered more than 600 participants from 12-14 July to discuss parish evangelisation with its theme drawn from John’s Gospel, “Make your home in me”. Keynote speakers over the three days included Archbishop Mark Coleridge, Cardinal John Dew from Wellington, Ron Huntley of the Divine Renovation network, Karolina Gunsser from Citipointe Church in Redcliffe, and Lana Turvey-Collins from the national facilitation team for the Plenary Council. As a former ‘outsider’ to the Church it has taken some twenty years to learn to live as a baptised person and still the learning continues. Through my own faith experience I have come to believe that the parish is essential to Christian growth and discipleship. Indeed, if we did not have parishes we would have to invent them – local communities of faith gathered around the Word and Eucharist where faith is given shape and social support, fostered into discipleship and then enters the world through our living witness.

As a former ‘outsider’ to the Church it has taken some twenty years to learn to live as a baptised person and still the learning continues. Through my own faith experience I have come to believe that the parish is essential to Christian growth and discipleship. Indeed, if we did not have parishes we would have to invent them – local communities of faith gathered around the Word and Eucharist where faith is given shape and social support, fostered into discipleship and then enters the world through our living witness. The Church is not for ourselves. In Pope Francis’ language, our community is called to be a ‘field hospital’ serving those who most need help now, the wounded and the lost. This is the antithesis of the self-referential Church. We are called to leave the ninety-nine to find the one, or in our Australian reality, leave the one to find the ninety-nine.

The Church is not for ourselves. In Pope Francis’ language, our community is called to be a ‘field hospital’ serving those who most need help now, the wounded and the lost. This is the antithesis of the self-referential Church. We are called to leave the ninety-nine to find the one, or in our Australian reality, leave the one to find the ninety-nine. In fact, inward looking churches create consumers with preferences, while outward looking churches create missionaries with larger hearts and stories to tell, stories about how Jesus has changed their life. This is the heart of an evangelised parish culture – one beggar telling another beggar how he found bread.

In fact, inward looking churches create consumers with preferences, while outward looking churches create missionaries with larger hearts and stories to tell, stories about how Jesus has changed their life. This is the heart of an evangelised parish culture – one beggar telling another beggar how he found bread. A classic example of the need to prioritise our mission over method can be found in the story of Kodak, the photography business established at the turn of the twentieth century, with the expressed purpose of preserving memories which is a seemingly indestructible mission.

A classic example of the need to prioritise our mission over method can be found in the story of Kodak, the photography business established at the turn of the twentieth century, with the expressed purpose of preserving memories which is a seemingly indestructible mission. A third horizon we can move toward in forming evangelising parishes is structures that support the mission. We want to grow but many parishes are not necessarily structured to grow. There can be literally “no room in the inn” for change.

A third horizon we can move toward in forming evangelising parishes is structures that support the mission. We want to grow but many parishes are not necessarily structured to grow. There can be literally “no room in the inn” for change. The fourth horizon we can move towards is putting mission into action, perhaps the hardest pilgrimage of all. As a friend once shared, conferences can sometimes be a bit like this: “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit” and when we get home, it is more “… as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be, world without end”.

The fourth horizon we can move towards is putting mission into action, perhaps the hardest pilgrimage of all. As a friend once shared, conferences can sometimes be a bit like this: “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit” and when we get home, it is more “… as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be, world without end”.